Testing libraries is important - who knew?!

25 Sep 2010Four years and a half ago, I was working on a pet game project which used XML format as intermediate storage format. Initially we used TinyXML, but I got tired of its interface and horrible parsing performance, and found pugxml. It was somewhat faster, with the interface which was somewhat better, but still - it was very rough. I decided to slightly change the library, improving performance and design along the way. Thus pugixml was born.

Little did I know at the time, that in five years I’d still be working on the same code. The amount of code and documentation is nearing a megabyte (the library itself is 280 kb, the rest is samples, tests and documentation), the revision number is 750+, hardly any original code is left untouched - it’s not a weekend affair anymore, that’s for sure.

In 2006 I took a very different approach to programming; initially the library had no tests at all. When I started developing an XPath implementation, I worked with a set of simple expressions in a single function in a single source file; once I considered my implementation to be complete, I made a Perl script that matched the test function output to the expected pattern to occasionally check it. Amazingly, I survived without tests for quite a while (the first proper test was added a year ago). Currently the amount of test code takes 1.5x the amount of library code, the code and platform coverage is, in my opinion, very good, and it’s time I wrote about testing.

There are different types of projects, and - at least in my opinion - automated testing is not mission critical for many, and not feasible for some. Often the requirements are vague and/or non-existent, like in game development, often they change on a weekly basis; a single feature may have three radically different implementation, with the first two being thrown out completely - you probably do not want to waste time testing that. Still, my experience in the application testing is rather limited, so I’ll discuss library testing.

When you’re making a library (or a cross-platform / cross-title engine), the situation is different. First, the code you’re writing is going to be used by many people on many projects/platforms. Whereas the bug in game code affects this game and can be fixed without any additional problems once it’s found, fixing the bug in the library has a huge latency - the users will be using the old version for a while. Some of them will find the bug, and either update to the new version, fix it themselves without telling you, or disregard it entirely (“The application crashes once in an hour? What, can’t you just restart it?”). The code you’ve written will fail to work on some of the platforms (we’re talking about C++ here) due to sloppy code, buggy libraries, buggy compilers (I’ve found many bugs in compilers/libraries during pugixml development. While most of them are in outdated software, there are still people out there who use pugixml with MSVC6), etc. - most of that you don’t care about when you’re delivering an application, but it will hurt you if you’re a library developer.

Why tests are that important, anyway? Is that because they make sure your code is correct?

No, unfortunately this is not true. You can’t even make sure your code is correct by proving it, because the proof will likely contain a bug (as a famous quote tells us, “Beware of bugs in the above code; I have only proved it correct, not tried it.”). The tests can pass because you’re lucky and they don’t expose that particular bug; the tests can have a bug; or perhaps you think that the tests are fine, and the function works, but the user/specification/other library/etc. expects a different behavior and thus the code is still incorrect.

All of the above are not the reasons to skip the tests, because the tests do improve the code quality substantially. And they do it because…

-

They force you to use your own code. Without that you’ll get hard-to-use interfaces, functions that a person once wrote and never ran (or perhaps he ran them once, and then the supporting code was restructured so that the code broke).

-

They force you to think about your own code. When you’re writing a test, you’re trying to test many different code paths (i.e. if you have a function that does a slow name lookup and a fast handle lookup, you’ll test both of them). While thinking about your code, you’ll likely think of some way to break it.

“What if I don’t delete this object?” “Uh-oh, this callback takes a non-const reference - what if I change the object?” “This function sums the list elements - what if I pass the empty list?” “Hmm, I did not write code to deallocate strings - why isn’t there a memory leak?”

By thinking about your code, you’ll be able to better understand its internals and flaws, and eventually get a better version of the code.

- They give you a safety net. If you’re optimizing an algorithm, how do you know that it works the same way it did before? If you encounter a bug and fix it, how do you know that this bug will never appear again? If you have to upgrade to the next version of the library you’re using - how do you know what works the same was as before and what does not? How do you port your code to the new platform - does the old code work there? One possible answer to all of the above is automatic testing.

Yes, it won’t guarantee that everything works - but it’s the best you can do. Moreover, every time a bug is found, you should understand why it was not caught by your tests. Perhaps that branch of code was never tested - you should expand your tests. Or perhaps the object’s internal state got messed up - you can likely add validation code to catch such bugs earlier. Also, the bug is likely to have siblings - think about the similar code in the rest of the codebase, and add the relevant tests.

Now, there are different types of tests. The exact type of testing you’re doing should depend on the component in question - some components can be unit tested, some require functional tests (at work we have unit tests for some components, and screenshot-based tests for others). Often the results are impossible to verify analytically (i.e. an A.I. simulation), but you can do a smoke test. (which, I believe, is generally too weak for libraries, but can be applied to games with good results).

Since we’re talking about libraries, the majority of them do not require smoke tests - they be tested using a combination of unit and functional tests.

The first steps are easy - you get a testing framework, and start writing tests. The tests verify the functionality the code has to deliver, the new bug reports are converted to tests - everything is fine. It’s also easy to use - there is this special compilation mode which you have to toggle in the vcproj, then copy a couple of files to the bin folder, and then the application outputs the test log, which says ‘passed’ or ‘failed’ for each test, along with some useful debugging information - but it’s easy to grep for ‘fail’.

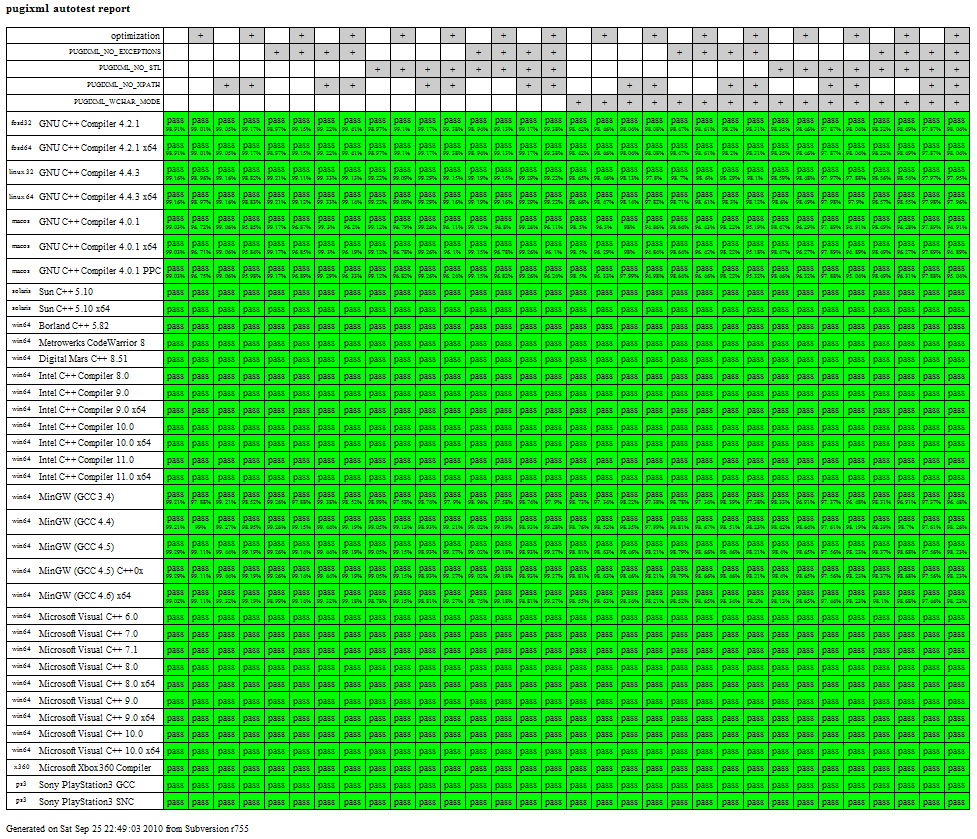

It seems that even after all these tests, there is a wide gap between testing and what I’ll call the serious testing. Next time I’ll discuss the features of the serious testing process, as I see it; for now let me tease you with a screenshot with pugixml automated test report (it’s clickable), taken while I was writing the post:

| « There's more than one way to map a cat | Taking testing seriously » |