Flavors of SIMD

17 Feb 2019During development of meshoptimizer a question that comes up relatively often is “should this algorithm use SIMD?”. The library is performance-oriented, but SIMD doesn’t always provide significant performance benefits - unfortunately, the use of SIMD can make the code less portable and less maintainable, so this tradeoff has to be resolved on a case by case basis. When performance is of utmost importance, such as vertex/index codecs, separate SIMD implementations for SSE and NEON instruction sets need to be developed and maintained. In other cases it’s helpful to understand how much SIMD can help to make the decision. Today we will go through the exercise of accelerating sloppy mesh simplifier, a new algorithm that was recently added to the library, using SSEn/AVXn instruction sets.

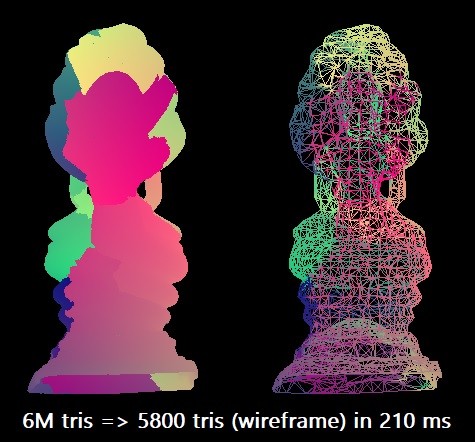

For our benchmark, we will be simplifying a 6M triangle “Thai Buddha” model, reducing it to 0.1% of the triangle count. We will use one compiler, Microsoft Visual Studio 2019, to target x64 architecture. The scalar algorithm can perform this simplification in about 210 ms1, using one thread of an Intel Core i7-8700K (running at ~4.4 GHz). Simplification can be parallelized in some cases by splitting a mesh into chunks, however this requires some extra connectivity analysis to be able to preserve chunk boundaries, so for now we’ll limit ourselves to pure SIMD optimizations.

Measure seven times

To understand our opportunities for optimization, let’s profile the code using Intel VTune; we’ll be running simplification 100 times to make sure we have enough profiling data.

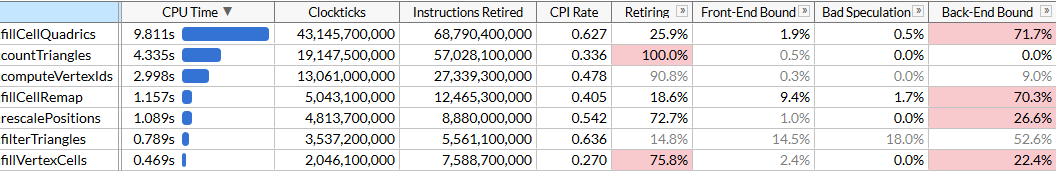

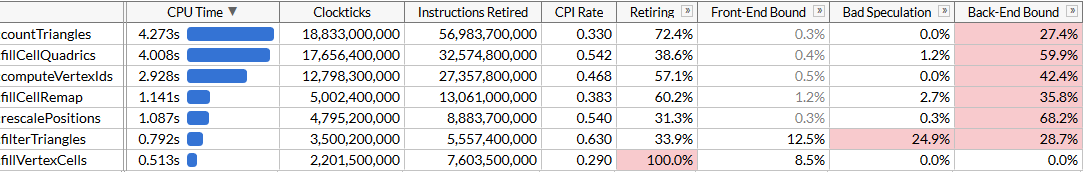

Here I’m using the microarchitecture exploration mode to get both the time each function takes as well as where the bottlenecks are. We can see that simplification is performed using a set of functions; each function is self-contained in that all of the time is spent in the function itself, not in any callees. The list of functions is sorted by the time they take, here’s the same list sorted by the order in which they execute, to make the algorithm easier to understand:

rescalePositionsnormalizes positions of all vertices into a unit cube to prepare for quantization usingcomputeVertexIdscomputeVertexIdscomputes a 30-bit quantized id for each vertex by taking a uniform grid of a given size and quantizing each axis to the grid (grid size fits into 10 bits, thus the id needs up to 30)countTrianglescomputes the approximate number of triangles that the simplifier would produce given a grid size, assuming that all vertices that lie in the same grid cell are merged togetherfillVertexCellsfills a table that maps each vertex to a cell that this vertex belongs to; all vertices with the same id map to the same cellfillCellQuadricsfills aQuadric(a symmetric 4x4 matrix) structure for each cell that represents the aggregate information about geometry contributing to the cellfillCellRemapcomputes a vertex index for each cell, picking one of the vertices that lies in this cell and minimizes the geometric distortion according to the error quadricfilterTrianglesoutputs the final set of triangles according to the vertex->cell->vertex mapping tables built earlier; naive mapping can produce ~5% duplicate triangles on average, so the function filters out duplicates.

computeVertexIds and countTriangles run multiple times - the algorithm determines the grid size to perform vertex merging by doing an accelerated binary search to reach the target triangle count, 6000 in this case, and computes the number of triangles that each grid size would generate for each iteration. Other functions run just once. On the file in question, it takes us 5 search passes to find the target grid size, that happens to be 403 in this case.

VTune helpfully tells us that the most expensive function is the function that computes quadrics, accounting for close to half of the total runtime of 21 seconds. This will be our first target for SIMD optimization.

Piecewise SIMD

Let’s look at the source of fillCellQuadrics to get a better idea of what it needs to compute:

static void fillCellQuadrics(Quadric* cell_quadrics, const unsigned int* indices, size_t index_count, const Vector3* vertex_positions, const unsigned int* vertex_cells)

{

for (size_t i = 0; i < index_count; i += 3)

{

unsigned int i0 = indices[i + 0];

unsigned int i1 = indices[i + 1];

unsigned int i2 = indices[i + 2];

unsigned int c0 = vertex_cells[i0];

unsigned int c1 = vertex_cells[i1];

unsigned int c2 = vertex_cells[i2];

bool single_cell = (c0 == c1) & (c0 == c2);

float weight = single_cell ? 3.f : 1.f;

Quadric Q;

quadricFromTriangle(Q,

vertex_positions[i0],

vertex_positions[i1],

vertex_positions[i2],

weight);

if (single_cell)

{

quadricAdd(cell_quadrics[c0], Q);

}

else

{

quadricAdd(cell_quadrics[c0], Q);

quadricAdd(cell_quadrics[c1], Q);

quadricAdd(cell_quadrics[c2], Q);

}

}

}

The function goes over all triangles, computes a quadric for each one, and adds it to the quadrics for each cell. Quadric is a symmetric 4x4 matrix which is represented as 10 floats:

struct Quadric

{

float a00;

float a10, a11;

float a20, a21, a22;

float b0, b1, b2, c;

};

Computing the quadric requires computing a plane equation for the triangle, building the quadric matrix and weighing it using the triangle area:

static void quadricFromPlane(Quadric& Q, float a, float b, float c, float d)

{

Q.a00 = a * a;

Q.a10 = b * a;

Q.a11 = b * b;

Q.a20 = c * a;

Q.a21 = c * b;

Q.a22 = c * c;

Q.b0 = d * a;

Q.b1 = d * b;

Q.b2 = d * c;

Q.c = d * d;

}

static void quadricFromTriangle(Quadric& Q, const Vector3& p0, const Vector3& p1, const Vector3& p2, float weight)

{

Vector3 p10 = {p1.x - p0.x, p1.y - p0.y, p1.z - p0.z};

Vector3 p20 = {p2.x - p0.x, p2.y - p0.y, p2.z - p0.z};

Vector3 normal =

{

p10.y * p20.z - p10.z * p20.y,

p10.z * p20.x - p10.x * p20.z,

p10.x * p20.y - p10.y * p20.x

};

float area = normalize(normal);

float distance = normal.x*p0.x + normal.y*p0.y + normal.z*p0.z;

quadricFromPlane(Q, normal.x, normal.y, normal.z, -distance);

quadricMul(Q, area * weight);

}

This looks like a lot of floating-point operations, and we should be able to implement them using SIMD. Let’s start by representing each vector as a 4-wide SIMD vector, and also let’s change the Quadric structure to have 12 floats instead of 10 so that it fits exactly into 3 SIMD registers2; we’ll also reorder the fields to make computations in quadricFromPlane more uniform:

struct Quadric

{

float a00, a11, a22;

float pad0;

float a10, a21, a20;

float pad1;

float b0, b1, b2, c;

};

Some of the computations here, notably the dot product needed to normalize the normal and compute the plane distance, don’t map well to earlier versions of SSE - fortunately, SSE4.1 introduced a dot product instruction that is quite handy here.

static void fillCellQuadrics(Quadric* cell_quadrics, const unsigned int* indices, size_t index_count, const Vector3* vertex_positions, const unsigned int* vertex_cells)

{

const int yzx = _MM_SHUFFLE(3, 0, 2, 1);

const int zxy = _MM_SHUFFLE(3, 1, 0, 2);

const int dp_xyz = 0x7f;

for (size_t i = 0; i < index_count; i += 3)

{

unsigned int i0 = indices[i + 0];

unsigned int i1 = indices[i + 1];

unsigned int i2 = indices[i + 2];

unsigned int c0 = vertex_cells[i0];

unsigned int c1 = vertex_cells[i1];

unsigned int c2 = vertex_cells[i2];

bool single_cell = (c0 == c1) & (c0 == c2);

__m128 p0 = _mm_loadu_ps(&vertex_positions[i0].x);

__m128 p1 = _mm_loadu_ps(&vertex_positions[i1].x);

__m128 p2 = _mm_loadu_ps(&vertex_positions[i2].x);

__m128 p10 = _mm_sub_ps(p1, p0);

__m128 p20 = _mm_sub_ps(p2, p0);

__m128 normal = _mm_sub_ps(

_mm_mul_ps(

_mm_shuffle_ps(p10, p10, yzx),

_mm_shuffle_ps(p20, p20, zxy)),

_mm_mul_ps(

_mm_shuffle_ps(p10, p10, zxy),

_mm_shuffle_ps(p20, p20, yzx)));

__m128 areasq = _mm_dp_ps(normal, normal, dp_xyz); // SSE4.1

__m128 area = _mm_sqrt_ps(areasq);

// masks the result of the division when area==0

// scalar version does this in normalize()

normal = _mm_and_ps(

_mm_div_ps(normal, area),

_mm_cmpneq_ps(area, _mm_setzero_ps()));

__m128 distance = _mm_dp_ps(normal, p0, dp_xyz); // SSE4.1

__m128 negdistance = _mm_sub_ps(_mm_setzero_ps(), distance);

__m128 normalnegdist = _mm_blend_ps(normal, negdistance, 8);

__m128 Qx = _mm_mul_ps(normal, normal);

__m128 Qy = _mm_mul_ps(

_mm_shuffle_ps(normal, normal, _MM_SHUFFLE(3, 2, 2, 1)),

_mm_shuffle_ps(normal, normal, _MM_SHUFFLE(3, 0, 1, 0)));

__m128 Qz = _mm_mul_ps(negdistance, normalnegdist);

if (single_cell)

{

area = _mm_mul_ps(area, _mm_set1_ps(3.f));

Qx = _mm_mul_ps(Qx, area);

Qy = _mm_mul_ps(Qy, area);

Qz = _mm_mul_ps(Qz, area);

Quadric& q0 = cell_quadrics[c0];

__m128 q0x = _mm_loadu_ps(&q0.a00);

__m128 q0y = _mm_loadu_ps(&q0.a10);

__m128 q0z = _mm_loadu_ps(&q0.b0);

_mm_storeu_ps(&q0.a00, _mm_add_ps(q0x, Qx));

_mm_storeu_ps(&q0.a10, _mm_add_ps(q0y, Qy));

_mm_storeu_ps(&q0.b0, _mm_add_ps(q0z, Qz));

}

else

{

// omitted for brevity, repeats the if() body

// three times for c0/c1/c2

}

}

}

There’s nothing particularly interesting in this code; we use unaligned loads/stores a lot here - while it’s possible to align the input Vector3 data, there doesn’t seem to be a noticeable penalty here for unaligned reads. Note that in the first half of the function that computes the normal and area, we aren’t utilizing vector units that well - our vectors have 3 components, and in some cases just one (see areasq/area/distance computation), whereas the hardware can perform 4 operations at once. Regardless, let’s see how much this helped.

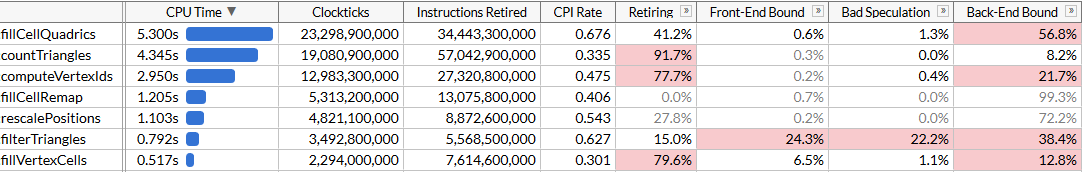

fillCellQuadrics now takes 5.3 seconds per 100 runs instead of 9.8, which saves ~45 ms for one simplification run - not bad, but somewhat underwhelming. Besides using just 3 components out of 4 in many instructions, we also are using dot product that has a pretty hefty latency. If you’ve written any SIMD code before, you know that the right way to compute dot products…

When’s the last time you had one quadric?

… is to compute four of them at once. Instead of storing one normal vector in one SIMD register, we’ll use 3 registers - one will store 4 x components of a normal vector, one will store y and the third will store z. For this to work, we need to have 4 vectors to work with at once - which means we’ll be processing 4 triangles at once.

We’re dealing with a lot of arrays that are indexed dynamically - while normally it can help to pre-transpose your data to already have arrays of x/y/z components3, this will not work well with dynamic indexing so we’ll load 4 triangles worth of data as we normally do, and transpose the vectors using a handy _MM_TRANSPOSE macro.

In theory, a pure application of this principle would mean that we need to compute each component of the final 4 quadrics in its own SIMD register (e.g. we’d have __m128 Q_a00 which will have 4 a00 members of the final quadrics). In this case, the operations on quadrics lend themselves pretty nicely to 4-wide SIMD, and doing this transformation actually makes the code slower - so we’ll only transpose the initial vectors, and then transpose the plane equations back and run the exact same code we used to run to compute the quadrics, but repeated 4 times. Here’s how the code that computes the plane equations looks after this, with the remaining sections omitted for brevity:

unsigned int i00 = indices[(i + 0) * 3 + 0];

unsigned int i01 = indices[(i + 0) * 3 + 1];

unsigned int i02 = indices[(i + 0) * 3 + 2];

unsigned int i10 = indices[(i + 1) * 3 + 0];

unsigned int i11 = indices[(i + 1) * 3 + 1];

unsigned int i12 = indices[(i + 1) * 3 + 2];

unsigned int i20 = indices[(i + 2) * 3 + 0];

unsigned int i21 = indices[(i + 2) * 3 + 1];

unsigned int i22 = indices[(i + 2) * 3 + 2];

unsigned int i30 = indices[(i + 3) * 3 + 0];

unsigned int i31 = indices[(i + 3) * 3 + 1];

unsigned int i32 = indices[(i + 3) * 3 + 2];

// load first vertex of each triangle and transpose into vectors with components (pw0 isn't used later)

__m128 px0 = _mm_loadu_ps(&vertex_positions[i00].x);

__m128 py0 = _mm_loadu_ps(&vertex_positions[i10].x);

__m128 pz0 = _mm_loadu_ps(&vertex_positions[i20].x);

__m128 pw0 = _mm_loadu_ps(&vertex_positions[i30].x);

_MM_TRANSPOSE4_PS(px0, py0, pz0, pw0);

// load second vertex of each triangle and transpose into vectors with components

__m128 px1 = _mm_loadu_ps(&vertex_positions[i01].x);

__m128 py1 = _mm_loadu_ps(&vertex_positions[i11].x);

__m128 pz1 = _mm_loadu_ps(&vertex_positions[i21].x);

__m128 pw1 = _mm_loadu_ps(&vertex_positions[i31].x);

_MM_TRANSPOSE4_PS(px1, py1, pz1, pw1);

// load third vertex of each triangle and transpose into vectors with components

__m128 px2 = _mm_loadu_ps(&vertex_positions[i02].x);

__m128 py2 = _mm_loadu_ps(&vertex_positions[i12].x);

__m128 pz2 = _mm_loadu_ps(&vertex_positions[i22].x);

__m128 pw2 = _mm_loadu_ps(&vertex_positions[i32].x);

_MM_TRANSPOSE4_PS(px2, py2, pz2, pw2);

// p1 - p0

__m128 px10 = _mm_sub_ps(px1, px0);

__m128 py10 = _mm_sub_ps(py1, py0);

__m128 pz10 = _mm_sub_ps(pz1, pz0);

// p2 - p0

__m128 px20 = _mm_sub_ps(px2, px0);

__m128 py20 = _mm_sub_ps(py2, py0);

__m128 pz20 = _mm_sub_ps(pz2, pz0);

// cross(p10, p20)

__m128 normalx = _mm_sub_ps(

_mm_mul_ps(py10, pz20),

_mm_mul_ps(pz10, py20));

__m128 normaly = _mm_sub_ps(

_mm_mul_ps(pz10, px20),

_mm_mul_ps(px10, pz20));

__m128 normalz = _mm_sub_ps(

_mm_mul_ps(px10, py20),

_mm_mul_ps(py10, px20));

// normalize; note that areasq/area now contain 4 values, not just one

__m128 areasq = _mm_add_ps(

_mm_mul_ps(normalx, normalx),

_mm_add_ps(

_mm_mul_ps(normaly, normaly),

_mm_mul_ps(normalz, normalz)));

__m128 area = _mm_sqrt_ps(areasq);

__m128 areanz = _mm_cmpneq_ps(area, _mm_setzero_ps());

normalx = _mm_and_ps(_mm_div_ps(normalx, area), areanz);

normaly = _mm_and_ps(_mm_div_ps(normaly, area), areanz);

normalz = _mm_and_ps(_mm_div_ps(normalz, area), areanz);

__m128 distance = _mm_add_ps(

_mm_mul_ps(normalx, px0),

_mm_add_ps(

_mm_mul_ps(normaly, py0),

_mm_mul_ps(normalz, pz0)));

__m128 negdistance = _mm_sub_ps(_mm_setzero_ps(), distance);

// this computes the plane equations (a, b, c, d) for each of the 4 triangles

__m128 plane0 = normalx;

__m128 plane1 = normaly;

__m128 plane2 = normalz;

__m128 plane3 = negdistance;

_MM_TRANSPOSE4_PS(plane0, plane1, plane2, plane3);

The code got quite a bit longer; we’re now processing 4 triangles in each loop iteration - we no longer need any SSE4.1 instructions for that though, and we should be utilizing SIMD units better now. Did this actually help?

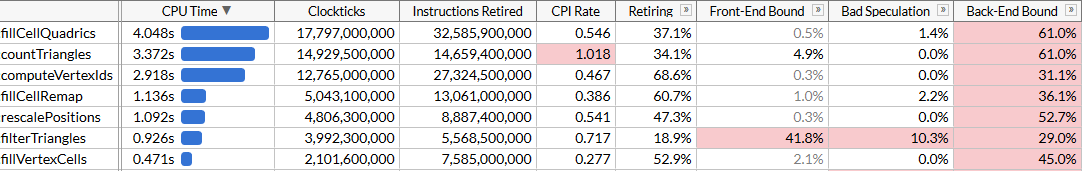

… ok, this wasn’t really worth it. We did get a tiny bit faster, and fillCellQuadrics is now almost exactly 2x faster compared to the non-SIMD function we started with, but it’s not clear if the significant increase in complexity justifies this. In theory we should be able to use AVX2 and process 8 triangles per loop iteration, however this requires even more manual loop unrolling4. Let’s try something else instead.

AVX2 = SSE2 + SSE2

AVX2 is a somewhat peculiar instruction set. It gives you 8-wide floating point registers and allows to compute 8 operations using just one instruction; however, generally speaking instructions have the same behavior as two SSE2 instructions ran on two individual halves of the register5. For example, _mm_dp_ps computes a dot product between two SSE2 registers; _mm256_dp_ps computes two dot products between two halves of two AVX2 registers, so it’s limited to a 4-wide product for each half.

This often makes AVX2 code different from a general-purpose “8-wide SIMD”, but it works in our favor here - instead of trying to improve vectorization by transposing the 4-wide vectors, let’s go back to our first attempt at SIMD and unroll the loop 2x, using AVX2 instructions instead of SSE2/SSE4. We’ll still need to load and store 4-wide vectors, but in general the code is just a result of replacing __m128 with __m256 and _mm_ with _mm256_ with a few tweaks:

unsigned int i00 = indices[(i + 0) * 3 + 0];

unsigned int i01 = indices[(i + 0) * 3 + 1];

unsigned int i02 = indices[(i + 0) * 3 + 2];

unsigned int i10 = indices[(i + 1) * 3 + 0];

unsigned int i11 = indices[(i + 1) * 3 + 1];

unsigned int i12 = indices[(i + 1) * 3 + 2];

__m256 p0 = _mm256_loadu2_m128(

&vertex_positions[i10].x,

&vertex_positions[i00].x);

__m256 p1 = _mm256_loadu2_m128(

&vertex_positions[i11].x,

&vertex_positions[i01].x);

__m256 p2 = _mm256_loadu2_m128(

&vertex_positions[i12].x,

&vertex_positions[i02].x);

__m256 p10 = _mm256_sub_ps(p1, p0);

__m256 p20 = _mm256_sub_ps(p2, p0);

__m256 normal = _mm256_sub_ps(

_mm256_mul_ps(

_mm256_shuffle_ps(p10, p10, yzx),

_mm256_shuffle_ps(p20, p20, zxy)),

_mm256_mul_ps(

_mm256_shuffle_ps(p10, p10, zxy),

_mm256_shuffle_ps(p20, p20, yzx)));

__m256 areasq = _mm256_dp_ps(normal, normal, dp_xyz);

__m256 area = _mm256_sqrt_ps(areasq);

__m256 areanz = _mm256_cmp_ps(area, _mm256_setzero_ps(), _CMP_NEQ_OQ);

normal = _mm256_and_ps(_mm256_div_ps(normal, area), areanz);

__m256 distance = _mm256_dp_ps(normal, p0, dp_xyz);

__m256 negdistance = _mm256_sub_ps(_mm256_setzero_ps(), distance);

__m256 normalnegdist = _mm256_blend_ps(normal, negdistance, 0x88);

__m256 Qx = _mm256_mul_ps(normal, normal);

__m256 Qy = _mm256_mul_ps(

_mm256_shuffle_ps(normal, normal, _MM_SHUFFLE(3, 2, 2, 1)),

_mm256_shuffle_ps(normal, normal, _MM_SHUFFLE(3, 0, 1, 0)));

__m256 Qz = _mm256_mul_ps(negdistance, normalnegdist);

After this we could take each 128-bit half of the resulting Qx/Qy/Qz vectors and run the same code we used to run to add quadrics; instead, we’ll assume that if one triangle has all three vertices in the same cell (single_cell == true), then it’s likely that the other triangle has all three vertices in one cell, possibly a different one, and perform the final quadric aggregation using AVX2 as well:

unsigned int c00 = vertex_cells[i00];

unsigned int c01 = vertex_cells[i01];

unsigned int c02 = vertex_cells[i02];

unsigned int c10 = vertex_cells[i10];

unsigned int c11 = vertex_cells[i11];

unsigned int c12 = vertex_cells[i12];

bool single_cell =

(c00 == c01) & (c00 == c02) &

(c10 == c11) & (c10 == c12);

if (single_cell)

{

area = _mm256_mul_ps(area, _mm256_set1_ps(3.f));

Qx = _mm256_mul_ps(Qx, area);

Qy = _mm256_mul_ps(Qy, area);

Qz = _mm256_mul_ps(Qz, area);

Quadric& q00 = cell_quadrics[c00];

Quadric& q10 = cell_quadrics[c10];

__m256 q0x = _mm256_loadu2_m128(&q10.a00, &q00.a00);

__m256 q0y = _mm256_loadu2_m128(&q10.a10, &q00.a10);

__m256 q0z = _mm256_loadu2_m128(&q10.b0, &q00.b0);

_mm256_storeu2_m128(&q10.a00, &q00.a00, _mm256_add_ps(q0x, Qx));

_mm256_storeu2_m128(&q10.a10, &q00.a10, _mm256_add_ps(q0y, Qy));

_mm256_storeu2_m128(&q10.b0, &q00.b0, _mm256_add_ps(q0z, Qz));

}

else

{

// omitted for brevity

}

The resulting code is simpler, shorter and faster than our failed SSE2 approach:

Of course, we didn’t get 8x faster than our original scalar code with AVX2, we’re just 2.45x faster. Our loads and stores are still 4-wide since we’re forced to work with inconvenient memory layout due to dynamic indexing, and the computations aren’t optimal for SIMD - but with this change, fillCellQuadrics is no longer the top on our profile, and we should focus on other functions.

Gather ‘round, children

We saved 4.8 seconds off our test run (48 msec per simplification run), and our top offender is now countTriangles. The function is seemingly simple, but it does run 5 times instead of just once, so it makes sense that it would account for disproportionately more time:

static size_t countTriangles(const unsigned int* vertex_ids, const unsigned int* indices, size_t index_count)

{

size_t result = 0;

for (size_t i = 0; i < index_count; i += 3)

{

unsigned int id0 = vertex_ids[indices[i + 0]];

unsigned int id1 = vertex_ids[indices[i + 1]];

unsigned int id2 = vertex_ids[indices[i + 2]];

result += (id0 != id1) & (id0 != id2) & (id1 != id2);

}

return result;

}

It iterates over all original triangles, and computes the number of non-degenerate triangles by comparing vertex ids. It’s not immediately clear how to make this use SIMD… unless you use gathers.

AVX2 is the instruction set that introduced a family of gather/scatter instructions to x64 SIMD; each instruction can take a vector register that contains 4 or 8 indices, and perform 4 or 8 loads or stores simultaneously. If we could use gathers here, we could load 3 indices, perform gather on all of them at once (or in groups of 4 or 8), and compare the results. Gathers have historically been pretty slow on Intel CPUs, however let’s try this. To make gathers easier to do we’ll load 8 triangles worth of index data, transpose the vectors similarly to our earlier attempt, and do the comparisons on respective elements of each vector:

for (size_t i = 0; i < (triangle_count & ~7); i += 8)

{

__m256 tri0 = _mm256_loadu2_m128(

(const float*)&indices[(i + 4) * 3 + 0],

(const float*)&indices[(i + 0) * 3 + 0]);

__m256 tri1 = _mm256_loadu2_m128(

(const float*)&indices[(i + 5) * 3 + 0],

(const float*)&indices[(i + 1) * 3 + 0]);

__m256 tri2 = _mm256_loadu2_m128(

(const float*)&indices[(i + 6) * 3 + 0],

(const float*)&indices[(i + 2) * 3 + 0]);

__m256 tri3 = _mm256_loadu2_m128(

(const float*)&indices[(i + 7) * 3 + 0],

(const float*)&indices[(i + 3) * 3 + 0]);

_MM_TRANSPOSE8_LANE4_PS(tri0, tri1, tri2, tri3);

__m256i i0 = _mm256_castps_si256(tri0);

__m256i i1 = _mm256_castps_si256(tri1);

__m256i i2 = _mm256_castps_si256(tri2);

__m256i id0 = _mm256_i32gather_epi32((int*)vertex_ids, i0, 4);

__m256i id1 = _mm256_i32gather_epi32((int*)vertex_ids, i1, 4);

__m256i id2 = _mm256_i32gather_epi32((int*)vertex_ids, i2, 4);

__m256i deg = _mm256_or_si256(

_mm256_cmpeq_epi32(id1, id2),

_mm256_or_si256(

_mm256_cmpeq_epi32(id0, id1),

_mm256_cmpeq_epi32(id0, id2)));

result += 8 - _mm_popcnt_u32(_mm256_movemask_epi8(deg)) / 4;

}

_MM_TRANSPOSE8_LANE4_PS macro is an AVX2 equivalent of _MM_TRANSPOSE4_PS that’s not present in the standard header but is easy to derive; it takes 4 AVX2 vectors and transposes two 4x4 matrices that they represent independently:

#define _MM_TRANSPOSE8_LANE4_PS(row0, row1, row2, row3) \

do { \

__m256 __t0, __t1, __t2, __t3; \

__t0 = _mm256_unpacklo_ps(row0, row1); \

__t1 = _mm256_unpackhi_ps(row0, row1); \

__t2 = _mm256_unpacklo_ps(row2, row3); \

__t3 = _mm256_unpackhi_ps(row2, row3); \

row0 = _mm256_shuffle_ps(__t0, __t2, _MM_SHUFFLE(1, 0, 1, 0)); \

row1 = _mm256_shuffle_ps(__t0, __t2, _MM_SHUFFLE(3, 2, 3, 2)); \

row2 = _mm256_shuffle_ps(__t1, __t3, _MM_SHUFFLE(1, 0, 1, 0)); \

row3 = _mm256_shuffle_ps(__t1, __t3, _MM_SHUFFLE(3, 2, 3, 2)); \

} while (0)

We have to transpose the vectors using floating-point register operations because of some idiosyncrasies in SSE2/AVX2 instruction sets. We also load data a bit sloppily; however, it seems like this mostly doesn’t matter because we’re bound by the performance of gather:

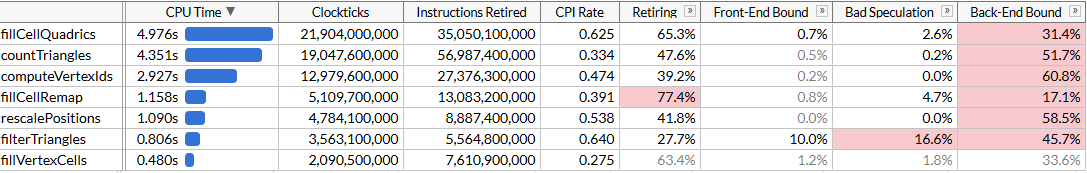

countTriangles does run ~27% faster now, and note that CPI - cycles per instruction - is now pretty abysmal; we’re dispatching ~4x less instructions but gather instructions take a lot of time. It’s great that they help us run a bit faster, but of course the performance gains are somewhat underwhelming. We did manage to get under fillCellQuadrics in profile, which brings us to our last function in the top we haven’t looked at yet.

Chapter 6, where things are as they should be

computeVertexIds is the last remaining function we’ll look at today - it runs 6 times during our algorithm so it’s also a great target for optimization. This function is the first one that actually looks like it should map cleanly to SIMD:

static void computeVertexIds(unsigned int* vertex_ids, const Vector3* vertex_positions, size_t vertex_count, int grid_size)

{

assert(grid_size >= 1 && grid_size <= 1024);

float cell_scale = float(grid_size - 1);

for (size_t i = 0; i < vertex_count; ++i)

{

const Vector3& v = vertex_positions[i];

int xi = int(v.x * cell_scale + 0.5f);

int yi = int(v.y * cell_scale + 0.5f);

int zi = int(v.z * cell_scale + 0.5f);

vertex_ids[i] = (xi << 20) | (yi << 10) | zi;

}

}

After all other optimizations we’ve explored here we know what we need to do - we need to unroll the loop 4 or 8 times, since it doesn’t make any sense to try to accelerate just one iteration, transpose vector components, and perform the computation in parallel on all of them. Let’s do this with AVX2, processing 8 vertices at a time:

__m256 scale = _mm256_set1_ps(cell_scale);

__m256 half = _mm256_set1_ps(0.5f);

for (size_t i = 0; i < (vertex_count & ~7); i += 8)

{

__m256 vx = _mm256_loadu2_m128(

&vertex_positions[i + 4].x,

&vertex_positions[i + 0].x);

__m256 vy = _mm256_loadu2_m128(

&vertex_positions[i + 5].x,

&vertex_positions[i + 1].x);

__m256 vz = _mm256_loadu2_m128(

&vertex_positions[i + 6].x,

&vertex_positions[i + 2].x);

__m256 vw = _mm256_loadu2_m128(

&vertex_positions[i + 7].x,

&vertex_positions[i + 3].x);

_MM_TRANSPOSE8_LANE4_PS(vx, vy, vz, vw);

__m256i xi = _mm256_cvttps_epi32(

_mm256_add_ps(_mm256_mul_ps(vx, scale), half));

__m256i yi = _mm256_cvttps_epi32(

_mm256_add_ps(_mm256_mul_ps(vy, scale), half));

__m256i zi = _mm256_cvttps_epi32(

_mm256_add_ps(_mm256_mul_ps(vz, scale), half));

__m256i id = _mm256_or_si256(

zi,

_mm256_or_si256(

_mm256_slli_epi32(xi, 20),

_mm256_slli_epi32(yi, 10)));

_mm256_storeu_si256((__m256i*)&vertex_ids[i], id);

}

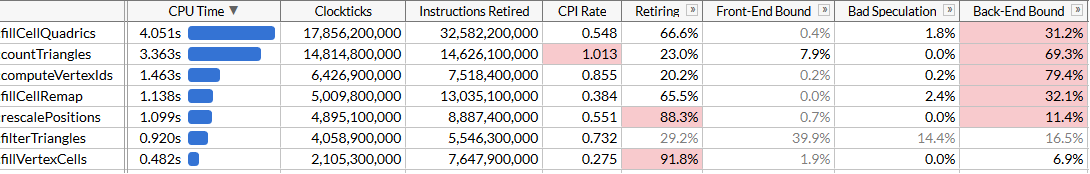

And look at the results:

We made computeVertexIds 2x faster, which, with all other optimizations combined, brings our total runtime to ~120 ms for one simplification run, which adds up to 50 million triangles/second.

It may look like we’re not getting the level of performance that we expected to see again - shouldn’t computeVertexIds improve more than 2x from introducing SIMD? To answer this, let’s try to see how much work this function is doing.

computeVertexIds is ran 6 times during the course of one simplification run - 5 times during the binary search, and once at the end to compute the final ids that are used for further processing. Each time this function processes 3M vertices, reading 12 bytes for each vertex and writing 4 bytes.

In total, this function processes 1800M vertices over 100 runs of the algorithm, reading 21 GB of data and writing 7 GB back. To process 28 GB of data in 1.46 seconds requires 19 GB/sec bandwidth. Running memcmp(block1, block2, 512 MB) on this system finishes in 45 msec, which makes me think that only about 22 GB/sec is achievable on a single core6. Essentially we’re now running close to memory speed and improving performance further would require packing our vertex data tighter so that positions require less than 12 bytes to store.

Conclusion

We’ve taken a pretty well optimized algorithm that could simplify very large meshes at a rate of 28 million triangles per second, and used SSE and AVX instruction sets to make it almost 2x faster, achieving 50 million triangles/second. Along this journey we had to explore different ways to apply SIMD - using SIMD registers to store 3-wide vectors, attempting to leverage SoA transposes, using AVX2 to store two 3-wide vectors, using gathers to load data slightly faster than it’s possible with scalar instructions and, finally, a straightforward application of AVX2 for stream processing.

SIMD often isn’t a good starting point for optimization - the sloppy simplifier went through many iterations of both algorithmic optimizations and micro-optimizations without the use of platform-specific instructions; however, at some point most other optimization opportunities are exhausted and, if performance is critical, SIMD is a fantastic tool to be able to use when necessary.

I’m not sure how many of these optimizations will end up in meshoptimizer master - after all, this was mostly an experiment to see how much it’s possible to push the hardware without drastically changing any algorithms involved. Hopefully this was informative and can give you ideas to optimize your code. The final source code for this article is available here; this work is based off meshoptimizer 99ab49, with Thai Buddha model available on Sketchfab.

-

This corresponds to ~28.5 million triangles/second which arguably is fast enough for practical purposes, but I was curious as to how much it’s possible to push the hardware here. ↩

-

In this case making the quadric structure larger by 8 bytes doesn’t seem to make a difference performance-wise; unaligned loads should be mostly running at the same speed as aligned loads these days so it likely doesn’t matter much one way or the other. ↩

-

Or rather what you should normally do is to pack data using small groups of SIMD registers, for example

float x[8], y[8], z[8]for each 8 vertices in your input data - this is known as AoSoA (arrays-of-structures-of-arrays) and gives a good balance between cache locality and ease of loading into SIMD registers. ↩ -

Ideally you should be able to use ISPC here for it to generate all this code - however, my naive attempts to get ispc to generate good code here didn’t work well. I wasn’t able to get it to generate optimal load/store sequences, instead it resorted to using gather/scatter which resulted in code that’s substantially slower than speed of light here. ↩

-

My understanding is that first CPUs that supported AVX2 literally implemented AVX2 by decoding each instruction into two or more micro-ops, so performance gains were limited to the instruction fetch phase. ↩

-

AIDA64 benchmark gets up to 31 GB/sec read speed on my system, but it uses multiple cores to get there. ↩

| « Is C++ fast? | Small, fast, web » |