Eight years at Roblox

02 Aug 2020I joined Roblox at the end of 2012 as a rendering engineer; I had just spent more than a year working on various titles from FIFA franchise after years of console game development and was becoming a bit tired of the “big game development”. My work on FIFA was as a contractor and I got an offer for a full-time position, but I also had a friend who worked at Roblox reach out and offer me to move to California and work on Roblox. I knew absolutely nothing about Roblox, but California was nice and my friend told me it would be awesome. The platform was so different (and so strange!) that I decided to take a chance - here I am, 8 years later, still working at Roblox and enjoying it. I started on my first full time job in April 2007 so at this point I’ve worked for 13 years in game development and 8 of them were at Roblox.

My memory works in interesting ways. I remember my interview pretty well, I remember having lunch at some place in San Mateo downtown near the Roblox HQ - a few people were at lunch including Roblox CEO David Baszucki and I remember him asking many questions about my thoughts about the engines and rendering, and distinctly remember not finishing most of my lunch because I talked most of the time. However I don’t really remember what was going through my head in regards to my perception of Roblox - why did I join besides just thinking I want to do something else for a change? Who knows, but I am glad I did.

I don’t really understand why Roblox is so successful - you can invent all sorts of reasons in retrospect but it’s hard to validate them, and if you came to anybody back in 2012 and asked for an investment to build a platform where all games are user generated and run on a custom engine with a custom toolset and all users participate in a giant virtual economy and …, I think you’d have gotten a blank stare.

But I do understand that I found the perfect place for me, especially at that point in my career - I enjoy working on game technology but I never liked working on actual games, and Roblox maximizes the number of developers who can use the technology you work on while maintaining a good autonomy and a very wide range of problems you’d need to solve. It’s very hard to get bored here.

I think I could talk for hours about Roblox - it somehow became a huge part of my life. I was very fortunate to join at the time when I did and witness the growth of our technology and business. I am really unsure of what the future holds but it’s hard to imagine what, if anything, comes after Roblox - I certainly don’t intend to leave any time soon…

So I thought it might be fun to do what I’ve planned to do for a year or more now, and to go over all decently sized projects I’ve ever worked on at Roblox. This is based on resummarizing and reliving the source control history, which tells me I’ve had 2752 changes that made it to our main branch, with merge commits counting as one, so, uh, this blog might be on a larger side. Hopefully this will be fun!

Before we begin, I just want to conclude this by saying that I’m very grateful to the Roblox leadership for treating me well, for all the friends and colleagues I made along the way, and for the wonderful Roblox community. The reason why I still enjoy what I do is because whenever I write about a new big thing I’m working on or a small feature or even a bug fix, it’s usually met with excitement which keeps me going. Thank you all from the bottom of my heart. I don’t think I could have done it without you and I hope this continues for as long as possible despite the current trying and uncertain times.

July 2012: Assorted fixes to rendering code

Notably including half-pixel offset fixes for Direct3D9 which I guess is a rite of passage for rendering engineers. The rendering code back then was based on OGRE rendering engine, so I had to learn that, and this was also my first time using OpenGL professionally - prior to that I’ve used Direct3D 9 and proprietary console APIs, and Direct3D 10/11 as a hobby.

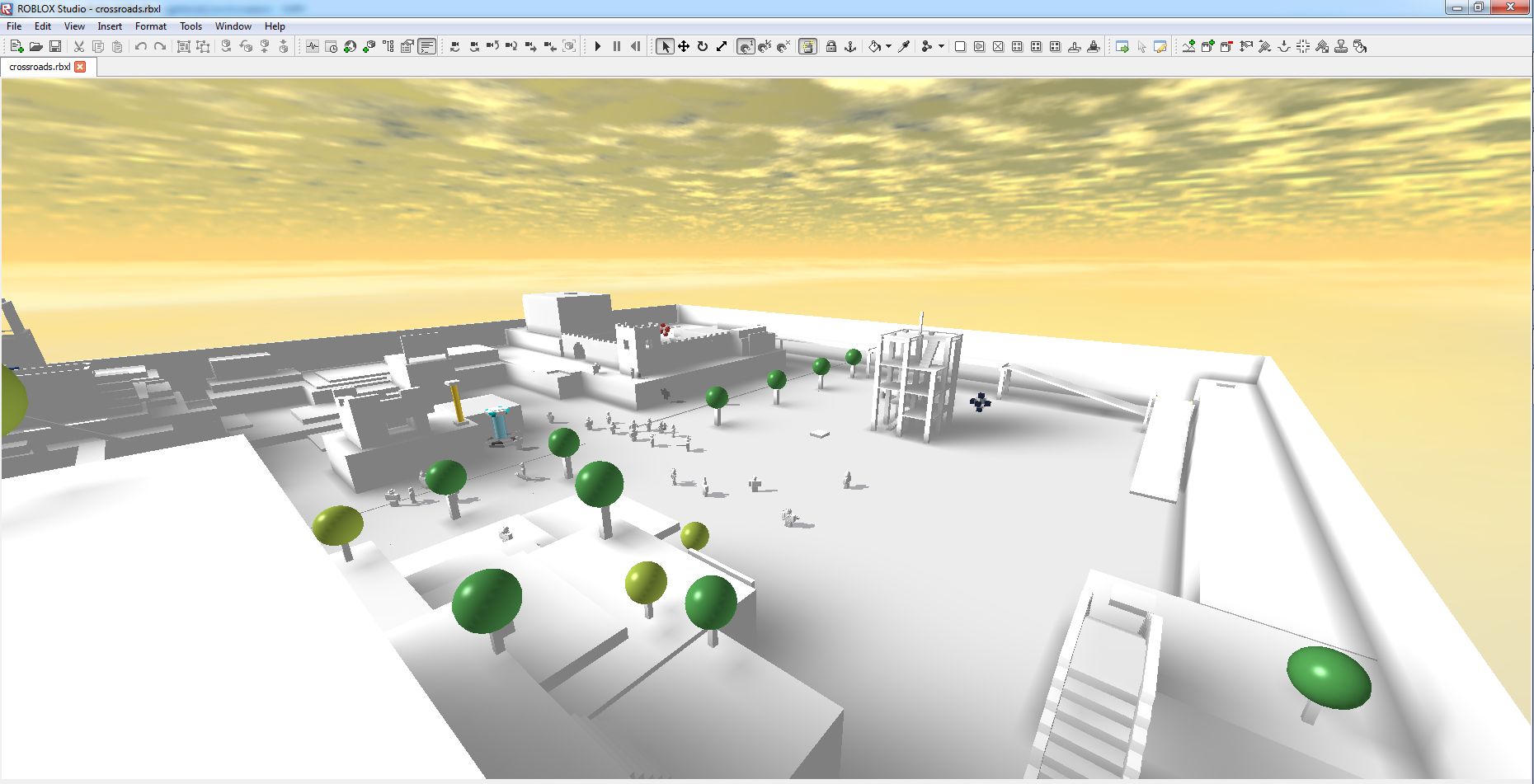

August 2012: Prototype new part rendering

Initially added for “100 player” project, in October it evolved to render all parts and continued to be used as part renderer until the introduction of instancing in 2018. Otherwise known as “featherweight parts”. This was further optimized and deployed around November 2012. Most of this code survived to this day but evolved over time, and is still used when instancing doesn’t apply.

The core idea in this system was to dynamically batch meshes together, for characters this would be based on the character model hierarchy, and for everything else the grouping is spatial. This allowed us to reduce the number of draw calls, which was a big concern due to both driver overhead and inefficiencies in OGRE.

This would pave the way for what eventually turned out to be a complete, but gradual, rewrite of the rendering stack. The main motivation for this was always performance - what we ended up let us port to mobile (the old rendering code was nowhere near fast enough even for relatively simple scenes), and break new grounds on the number of objects we could render in a frame.

August 2012: OGRE upgrade from 1.6 to 1.8

One of a few OGRE upgrades we’ve needed to do, this one was to get better GLES support. It was pretty painful to do those, just like any other big middleware update is. Read further to learn what happened to OGRE eventually…

One thing I remember from doing these is that documentation in source code makes the upgrade process that much more painful. I had scripts that changed the copyright years in headers back to whatever they were in our tree just to make merging less painful, but there was some OGRE upgrade where 70% of the changes were documentation, and this was very hard to get through.

The reason why these were challenging in general is that whenever we did an upgrade we had to a) merge our plentiful changes with the new code, b) gate dangerous parts of the upgrade with flags. We’ve used the same system of feature flags (we call them fast flags) since I joined Roblox which allows us to dynamically disable parts of the release based on metrics, but this requires actually isolating changes behind if statements selectively - which for OGRE was sometimes necessary as we didn’t know what the impact of some low level change in OpenGL code would be.

September 2012: First HLSL->GLSL shader compiler

Before this we had hand-translated shaders, which started to be painful to maintain. The first version of the pipeline used hlsl2glsl and glsl-optimizer (same as Unity back in the day). We are using version 3 today, see below!

Since this was done at the point where we used OGRE, the compiler would take HLSL files, preprocess and translate them to optimized GLSL, and save the resulting GLSL back to disk - which would then be loaded by OGRE directly through the material definition file. Eventually we replaced this with a binary shader pack that could store GLSL code for OpenGL and shader bytecode for other APIs, but back then we shipped HLSL and GLSL source and compiled HLSL code on device!

September 2012: F# scripts for HW statistics

Our equivalent of “Steam Hardware Survey” that went through SQL databases and coalesced various system information bits to help us understand the hardware at the time. This was during my era of obsession with F#, so it was written in F# instead of something like Python. We don’t use this anymore and don’t even have the SQL database in question!

We never published the resulting data, and I’m not sure how often we used it to make decisions, but it was fun to look at the number of graphics cards from various vendors or amount of RAM or resolution a typical Roblox user has.

September 2012: First exploit fix

Although I was hired as a rendering engineer, I had a lot of really deep low-level systems experience and as a consequence ended up engaging in both optimization work and security related work from the very beginning. I don’t do this anymore these days but I was often involved in the security work for the first 3 or 4 years. Now we fortunately have people who can do this full time and better than I could :)

September 2012: Character texture compositor

A second part of “100 player project”, necessary to render every character in one draw call (these were really expensive for us back in the day!). A side effect included some resolution sacrifices on character items that shirt creators aren’t fond of. The new system managed the atlas texture memory, rebaking humanoids far away to smaller textures to conserve texture memory. The compositor survived with minor changes to this day, although we’re now working on a new one.

The compositor was built in a very configurable fashion, allowing the high level code to specify the layout to bake, and managing all the complex asynchronous processing and budgeting by itself. This allowed us to switch the composit layout completely years later for R15.

October 2012: Assorted memory/performance work

At the end of 2012 we were actively working on the mobile port. Since then we’ve had to do a lot of work in a lot of different parts of the engine to make data structures smaller and algorithms - faster. Of course you’re never done with optimizations so we do this to this day. Curiously, our minimum spec on iOS stayed the same since the initial launch in 2012!

A fun fact is that even though we started with iPad 2 as the min. spec we discussed adding support to iPad 1 after launch. At the time there were a lot of people who couldn’t play Roblox on iOS on older hardware. However the performance characteristics of those devices were just… not good enough. You could touch the screen with the finger and pan the camera, and during panning you lost 30% of a single available core to the OS processing the touch. We decided to not add support for this, and 8 years later it seems like a great decision for sure :D

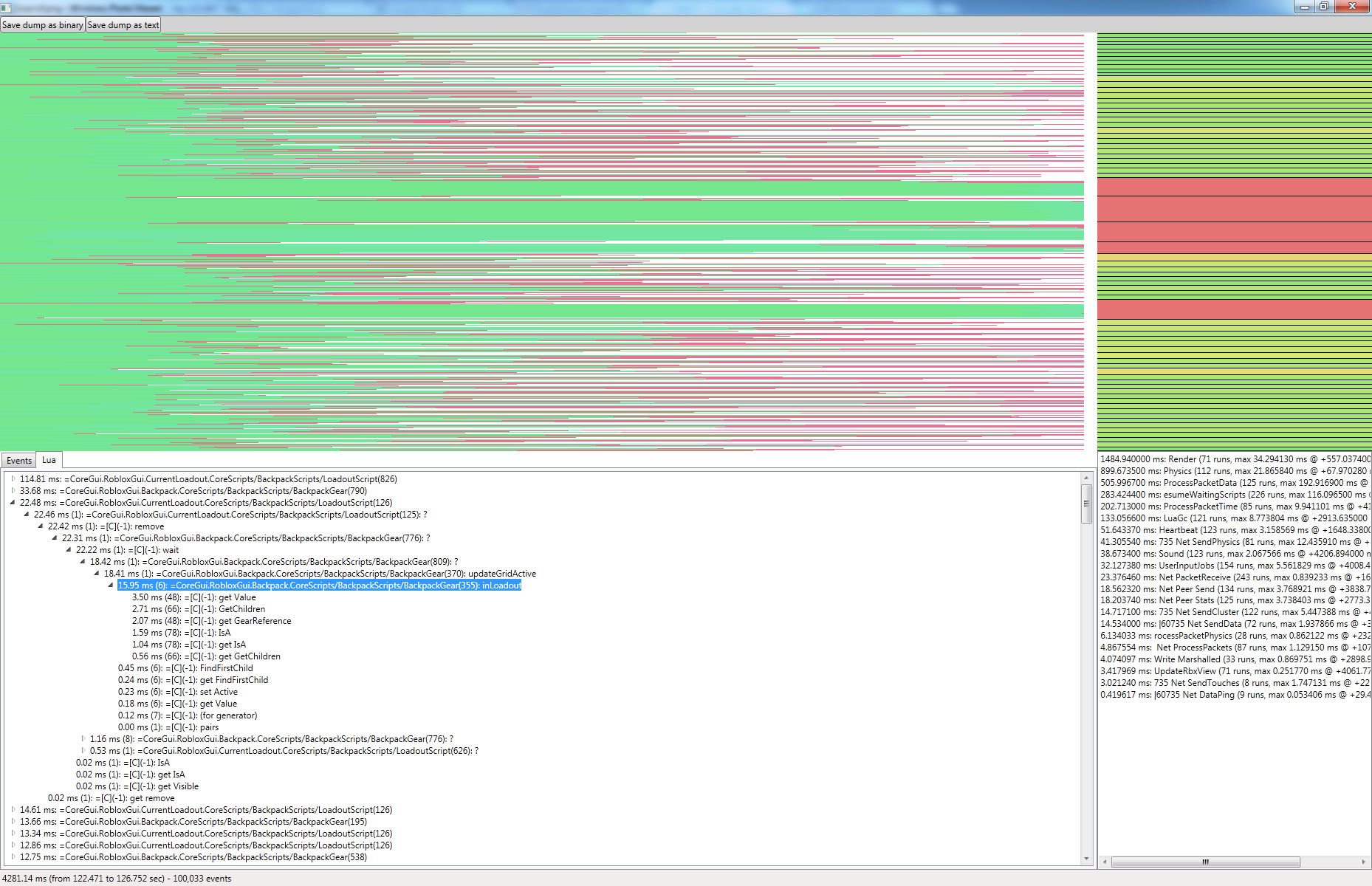

October 2012: Event-based profiler in F#

It was very hard to use Xcode Instruments to profile frame spikes on an iPad; to try to figure out how to get our performance to a better place on mobile, I wrote some ad-hoc code to dump all internal log events to a binary stream, and a desktop UI tool in F# and WPF to visualize it. This included a Lua profiler as well that could display profiles of Lua code in a traditional hierarchical aggregated view based on event data. This did not survive but curiously we ended up using a similar approach with microprofile years later.

November-December 2012: Finalize part rendering

What started in August as a character-only renderer that supported meshes, evolved into something that could render any part in Roblox the same way as old rendering code did. This was not easy, both because performance was really important in every part of the code, and because there’s a lot of corner cases that had to function pretty much as they did before. Except for perhaps the legacy cylinder rendering:

This code supported FFP as well, using matrix palette blending to efficiently render characters with rigid joints, and on desktop also came with vertex shaders that were carefully optimized to run faster on Intel GPUs without hardware vertex shading (through software vertex shading path). Also this implemented stencil shadows using GPU-based extrusion and CPU-based detection of silhouettes with dynamic index buffers. Fun times!

January 2013: Voxel lighting work begins

My memory is a bit fuzzy on this one but I think we were brainstorming possible ways to implement full scene shadows in a way that would work on mobile, and I’ve recently watched the presentation from Little Big Planet on how they did lighting on PS3 with voxel based computations; our CEO was part of the discussions and mentioned “what if all lighting was voxel based”, and the rest is history. The approach we ended up taking was very unique and distinct from many other voxel based implementations to my knowledge.

February 2013: Skylight and optimizations

In January voxel lighting engine got support for sun shadows and point/spot lights but it felt like on good GPU hardware we could get better results with other techniques, so we were looking for other things we can use voxels for. I don’t remember who came up with the idea but this is when skylight was implemented, which is a form of ambient occlusion with sky as a light source, and is very hard to do correctly without voxels.

To make voxel lighting practical I also rewrote all functions using hand coded SIMD (SSE2), including the voxelizer - lighting on CPU isn’t practical without this (this code was later translated to NEON for the iOS port).

The resulting lighting code survived up until FIB Phase 1 which added HDR support and changed voxelizer to use anisotropic occupancy, but is otherwise still used today.

March 2013: New materials

In an effort to redefine the way Roblox games look (back then we thought Roblox as a platform needs an art style), the work on new materials began. We used to use a random set of shaders including some procedural ones; this work replaced the shader framework with “surface shaders” (this is inspired by Aras P. work on Unity from around the same time; we use the resulting shader interfaces to this day although it’s not clear that they are actually pulling their weight, and if I did it today again I would not have gone that route), and implemented more traditional texture-based materials on top, ruining wood grain forever.

April 2013: Binary file format

Annoyed with the time it took our custom XML parser/serializer to work with large places, I designed and implemented a custom binary file format. It was chunk-based with per-chunk LZ4 compression and custom binary filters to preprocess the data to help LZ4; the format was structured to make reflection interop cheaper, and maximize loading performance. We use this as the main file format to this day, although the format got a few small tweaks (mainly extensions to handle cryptographic signatures and more efficient shared binary blobs). I’m still happy with the design but I’d slightly change the layout in a couple of places to make loading for very big places more cache-coherent, something that wasn’t as big of a concern back then. This can still be done today but requires small revisions to how some chunks represent data.

The initial rollout of this change was just for Play Solo, which saved the entire world to a file and loaded the result back into the new datamodel; this meant it was safe to release because no permanent data loss would occur. After this we gradually switched to using this format for publishing places, and eventually started using it for models (packages) as well. Today almost all semantically rich content on Roblox uses this format.

Ironically we did end up replacing our XML parser with a library of mine, pugixml, in 2019 - although the binary storage is still more performant and space efficient.

May 2013: OpenGL ES2 support

When we shipped our iOS port it was done with ES1 (FFP); this meant a lot of features didn’t work, including lighting which was becoming pretty important. OGRE support for ES2 was immature at the time, so this included a lot of fixes in OGRE code, and a fair amount of shader tweaks, plus the aforementioned NEON optimization for voxel lighting code to make it practical to run on a mobile device.

This change helped in the future work - after this landed we never used FFP on mobile, always using shaders to render content, which meant that we wouldn’t need to support ES1 for any technology upgrades, that as it turned out were waiting around the corner.

May 2013: Remove legacy part rendering code

The development of Roblox engine usually follows a tic-toc-tac pattern (okay we don’t actually have a name for this, but whatever). First we make a new awesome implementation of a subsystem that was in the need of being replaced. Then we work on that new implementation becoming better. Then we remove the legacy system to simplify maintenance. By this point we’ve switched all parts to render in the new cluster rendering path and the old code was ready to be removed. The commit says “removes 500 kb of C++ code, 400 kb of shader/material code, and 3 Mb of content/ textures. Also removes 17 rendering fast flags and 5 rendering log groups.” which felt pretty good at the time!

June 2013: Thumbnail rendering optimizations

The way we render thumbnails is with the same rendering code we usually use on the client, but it runs on our servers using a software renderer. This was inefficient because we used a slow software renderer (single-threaded without a JIT) and additionally we went through the setup/teardown of the entire engine for every new image; this was reworked to use a faster software renderer (which was mostly hard because building open-source software on Windows is a pain), and to reuse the same engine context for many thumbnails, which allowed us to dramatically cut the amount of servers we used. It’s comparatively rare that the work I do can be measured in money spent for the company so this felt good.

July 2013: New materials for real

… I guess in March I just did some preparatory work, and it’s in June when we actually started working on new shaders and new textures. There was a lot of back-n-forth with our artist to make sure the art can look good in-game but also not create too many issues for games using built-in materials completely counter to their intended purpose (e.g. using Sand colored in blue as water).

A big portion of work here though was a new UV layout for our terrain materials - we used a voxel based terrain that had a few distinct block types (block, wedges, corner wedges), and together with artists we came up with a new UV layout that was more uniformly distributing pixels in the texture to get good density everywhere.

July 2013: Point light shadows

I remember thinking about voxel lighting more and at some point realizing, well, we can do directional shadows from the sun, we can do point lights - why can’t we do both at the same time, so that every single light source can cast shadow? It turned out that the approach we used for the directional shadows could be adapted to work for point lights, and with some optimizations and tweaks the first version of the voxel lighting engine was finally complete. This would survive up until Future Is Bright Phase 1 which would ship at the end of 2018. This was finalized in September 2013 and optimized with SIMD:

Change 37700: SIMD shadow update now works, but I have no idea why.

Change 37701: SIMD shadow update works, and now I know why :) Still need more optimization

I love writing commit messages that straddle the border between “professional” and “fun”.

August 2013: New text renderer

Since all of the easy problems, such as part rendering and lighting, were solved, it was time to face the final rendering challenge: text.

Back then we used a prebaked bitmap (actually two) at two different sizes, and a very poorly written layout code that didn’t support kerning and didn’t handle spacing well. Instead I wrote an F# script (of course!) that baked lots of different sizes of a single font into a large atlas; to conserve texture space, I used a rectangle packer. At runtime the layout algorithm used kerning data to place glyphs at correct locations. This substantially improved text quality at most frequently used sizes, and would last for a few years up until internationalization became a priority and we had to start rendering the font atlas dynamically from TTF source. The layout algorithm would survive for a few more years up until we integrated Harfbuzz to do complex Unicode aware shaping - both of these were done by other people years later.

September 2013: Remote events

Continuing the trend of increasing the scope of work beyond just rendering, I’ve worked on the design and implementation of new remote events API, including fire-and-forget events and remote function calls (which are super nifty in Lua - because of coroutine support, you can just call a function in Lua, that call will be routed to the server, server will run the code and return the result, and your coroutine will continue running, almost oblivious to the time spent!). It was very hard to find good names for the APIs involved; we haven’t changed any of this since and I still struggle with what the correct function/event name is sometimes.

October 2013: Infinite terrain

Voxel terrain wasn’t very popular among our game developers. For a feature that took a lot of effort to develop and maintain this was unsatisfying, and I was trying to figure out “why”. One hypothesis was that the limited size (512x64x512 voxels I want to say?) made it too limiting; to remedy that I’ve worked on a new sparse voxel storage format and different replication mechanisms to allow arbitrarily large terrains. This took around a month to implement fully. This code no longer exists because I ended up throwing the old terrain out completely later - this is probably my largest body of work that just doesn’t exist in Roblox today, although if I hadn’t worked on that, smooth terrain would have likely taken longer and would be worse, because many ideas from that translated well.

During this work I also added TerrainRegion (a standalone object that could store voxel data) together with APIs for copy & paste - this part hasn’t changed since and is still available and useful.

November 2013: Implement RenderStepped callback

I don’t really remember much about this - I don’t think we had an API proposal process at the time so I think this just came up and we just did it, but this is a pretty significant event in retrospect because it started the general trend of giving Lua scripts much more agency; without this we could not have implemented cameras in Lua, for example, and some games today - for better or for worse - run a lot of their game loop in render stepped for minimal input latency. At this point we’ve already used a two-thread parallelization strategy where normally input->gameplay->render cycle is a 2-frame cycle on the CPU, but by using RenderStepped you can cut that short and have minimal latency for user interaction at some throughput cost.

December 2013: UI rendering optimizations

Somehow all games or engines I have ever worked with end up with UI consuming disproportionate amount of frame time, and ours is no exception :( Over the years I’ve had several points at which I snapped and committed a dozen performance improvements to make things faster, this is one of them; every time the changes weren’t necessarily transformative or really complex, but delivered solid performance gains by shaving ~10% or more at a time.

December 2013: Smooth terrain hack week

This was my first hack week - the 2012 hack week was held in July right before I joined, although I doubt I would have achieved much as I was very unfamiliar with the codebase. By this point I knew everything there was to know about our rendering system, OGRE, and terrain; I combined this knowledge to implement a prototype for new terrain that used Marching Cubes meshing of voxel distance field instead of blocky terrain we had, with support for geometric LOD (with gaps between LODs because hack week) and also added water with refraction and realtime reflections and geometric grass. Over the next few years I ended up shipping most of this, although the implementation was dramatically different (e.g. we don’t use marching cubes), and finally in 2019 somebody else shipped geometric grass (again with a very different implementation), marking my 2013 hack week fully live :D

January 2014: Mobile performance

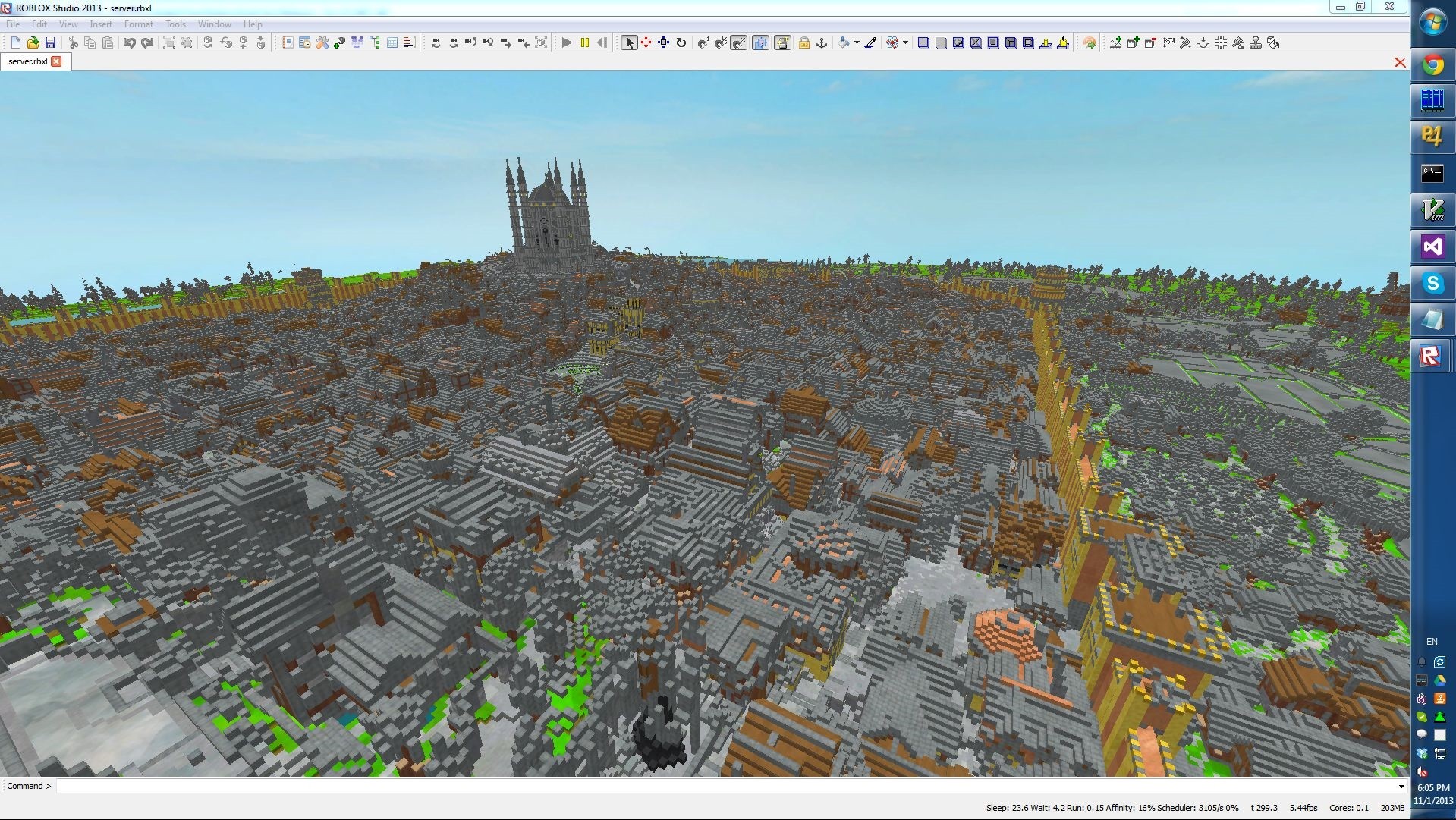

A continuing drive to get our rendering code faster and faster invited more optimization. I remember us using two internal games for profiling, one was made by an internal games team (we used to make games ourselves back then! We quickly realized that we’re a platform and that our community can make games better than we can though) and another by John Shedletsky, a name all Roblox readers would recognize. We were trying to get them to run at stable 30 FPS on iPad 2, which was challenging. A lot of small performance tweaks went in here but I was starting to become really frustrated with the amount of time we lost in OGRE and OpenGL driver. I was pretty sure a lot of OpenGL work wasn’t just because the driver wasn’t very fast (that problem would have to wait until the introduction of Metal), but also because OGRE’s GLES backend was very inefficient. We could have tried to optimize OGRE, but that codebase was so large and unwieldy to work with that a question had to be asked: do we need it?

So I spent one day to do an experiment: I set up an alternative GL-focused rendering path alongside OGRE. This took just a day because I focused on just getting part rendering to work, and only converting the actual render loop away from OGRE - using OGRE scaffolding to manage resources, and then getting OpenGL resource ids out into our own code. There were no special optimizations after that, I just wrote code that I thought was very simple and minimal - just do the state setup that needs to be done in the simplest way. The results were that by rewriting a portion of the rendering frame that took 13 ms in OGRE, we could replicate it in just 3 ms in our renderer.

This made the decision of what to do next obvious.

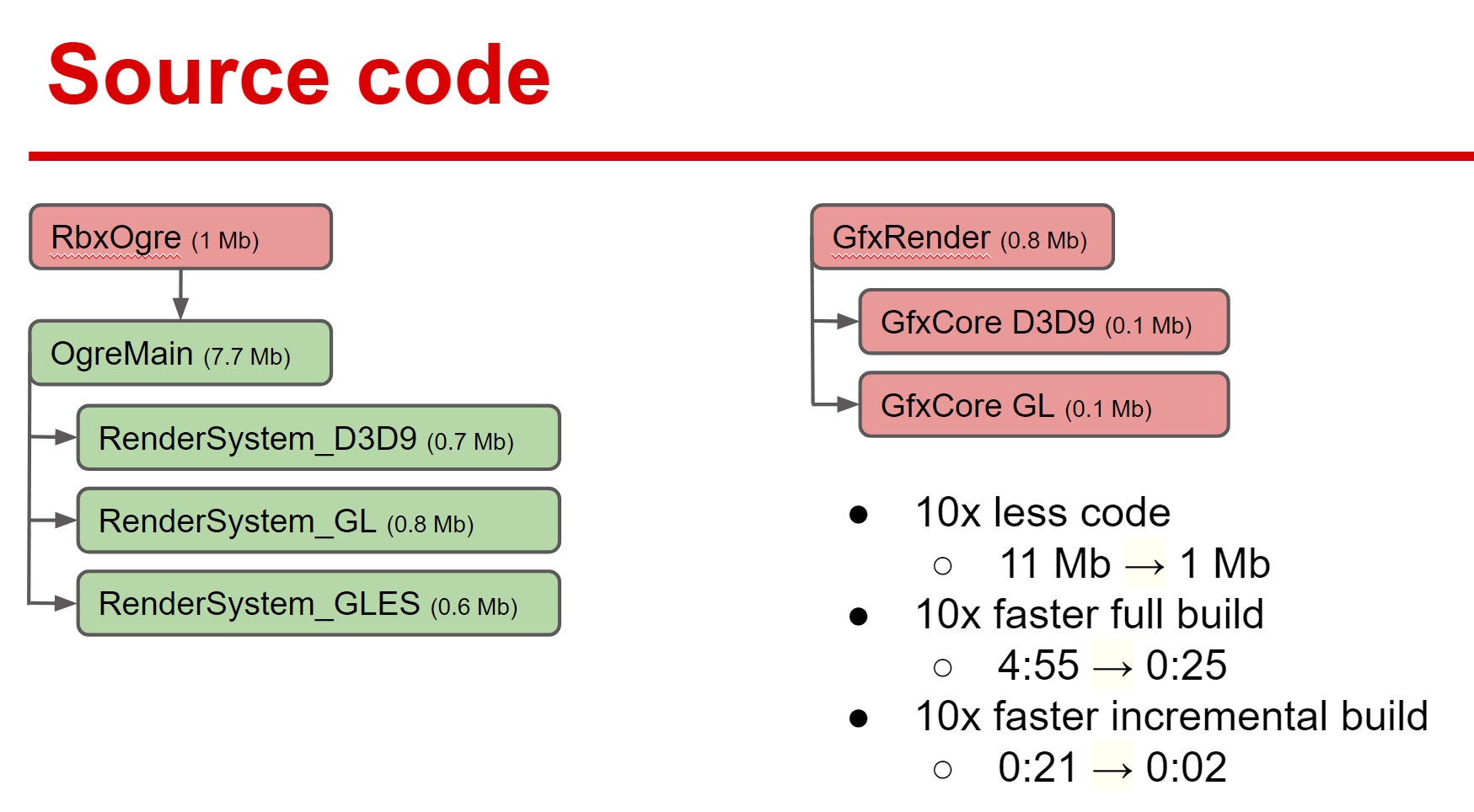

February-April 2014: New rendering engine

We decided to completely remove OGRE as a dependency in favor of our own rendering engine. To simplify the matters a bit, we decided on just two rendering backends, Direct3D 9 (with FFP support) and a combined OpenGL backend with desktop and mobile “modes”, to support macOS and iOS, without FFP support.

The fact that we already used OGRE in the most minimal way possible made things easier - we didn’t need to port the animation system, all the shaders we used were our own, etc. The only significant high level component we used from OGRE was the particle system, and we had an engineer start on redoing that - I focused on everything else, including defining a new graphics API abstraction layer, implementing Direct3D9 and OpenGL backends for that, working on a basic material system and render op list, etc.

This had to be done side by side with the old engine, so we copied the high level code that used OGRE and started reworking that. A big painpoint when working with OGRE was getting access to any hardware functionality (I don’t remember details too well but one thing I remember is render targets not being structured very well), so I spent a bit of time thinking about the graphics abstraction - but not too much, as we could iterate on that in the future (and we did!). A big focus was on usability (it had to be reasonably easy to use it from our high level rendering code) and leanness (for performance and sanity reasons we wanted the concepts in the abstraction to map mostly 1 to 1 to the underlying implementations).

Because mobile was a focus, we ended up inheriting some concepts from OpenGL (like Framebuffer, ShaderProgram, Geometry, uniform handles, etc.). Some of these survived to this day and continue being useful for other APIs; some parts of the abstraction saw major changes, for example we fully transitioned to uniform buffer style interface after a Direct3D 11 port, and render pass based interface during a Metal port. The abstraction continues to slowly evolve over time, and one part I’m super excited about is that since the initial release, the abstraction actually became leaner and more straightforward to implement (for example, we used to have a distinction between Renderbuffers and Textures, and now we just have Textures).

This was the right time to do this change. We already implemented all critical high level rendering components by that time, so we knew exactly what to focus on - but this was back when we only had two rendering engineers, myself included, and so we didn’t have to stall major projects by rebuilding the foundation of the engine.

The new code took around 2.5 months to complete and ship; the results were fantastic - much lower CPU overhead, much simpler code base, much faster builds and smaller distribution size - it was a massive win along every single possible axis. Most of that code still exists and is in active use today, some parts had to be expanded or improved as we gained more graphics API - we went from supporting just two APIs to supporting five.

The epic for the change was named

US22804: Do you know how to K.I.L.L. an OGRE?

Which in addition to being an obvious pun on “ogre” is a reference to Death Note which I watched for the first time around that time and rewatched many times since.

May 2014: Lua security fixes

During this period I’ve submitted an unusual number of various security mitigations for different exploits so while I don’t remember this it must have become a focus.

In addition to that in May and June I’ve started helping with our Android port - something that was made much easier due to our new rendering engine, as OGRE support for EGL was incomplete at the time.

May 2014: Data persistence data loss

Something that I completely forgot about since but was reminded by a page on Roblox trivia wiki is that I was responsible for a data loss in our data persistence system. The core issue was caused by an innocuous code change that refactored some XML serialization logic in an effort to make sure that at all callsites we correctly use binary file format for saving when requested. We had code that could serialize Roblox instances as part of a larger XML container, used for web API serialization - I mistakenly assumed this was part of web API support code that we didn’t need anymore.

Unfortunately, this was actually important for games that used our data persistence system that was in the process of being replaced by newer data stores. This only affected games that stored instance data (thankfully, most games used exclusively primitive types); unfortunately, we didn’t have unit tests for the system and our manual regression test only used primitive types. Additionally manual tests on our pre-production test environments that relied on backend data were often flaky due to environment stability issues (something that we’ve largely solved in 2020 by switching to testing using production infrastructure and pre-release client/server builds instead of relying on separate environments).

What made the issue damaging is that the legacy system in question treated all errors during data loading as “data is absent, start from scratch”. This was due to the fact that the web endpoint returned a status code 404 for non-existent data, which resulted in an exception propagated through the client-side code; instead of special casing that error code, and disabling data saving for any subsequent save, the code assumed any error is a 404 error and joyfully proceeded to start with an empty data blob, saving it when the player quit the game.

This was further aggravated by the release timing - we used to release the client & server at 9 PM at night; any issue that was discovered immediately after the release would lead to the release rollback, but this issue was only discovered a few hours after the release by a developer who reported it to us - at which point everybody was sound asleep and all players who played affected games that night would lose their game data irrecoverably (as the system in question also had no backups). This also isn’t a problem in 2020 as we switched the release process to one that’s safe to do at any time of day and we now release in the morning so we can react to any issue that’s discovered hours after the release immediately.

Needless to say I’ve learned a few things about refactoring legacy code, testing and deployment processes, etc. I think this is the only destructive or negative thing I’ve done during my time at Roblox, and it felt terrible at the time. Time heals all wounds though!

June 2014: Lua linter

I’m not sure how this came about, but I think I was just thinking how we can make it easier for people to write correct Lua code, and an obvious problem was lack of any sort of static analysis / linting. luacheck was something that existed at the time, but it wasn’t very fast and I thought we needed a tool that’s written in C++ for this.

Amazingly it looks like the first change for this tried to do static analysis on compiled Lua bytecode, a fact that I completely forgot until today, but I quickly changed gears and started working on a Lua->AST parser. I’ve written many parsers before that and some of them were very high performance, so I knew what I was doing pretty well.

After implementing the parser, I implemented a few static analysis rules based on AST; some of these later shipped as Script Analysis Widget (which required a fair amount of Qt work that a long-time Studio engineer helped me with), and some were experimental, such as a data flow analysis, that were incomplete and never went live.

This work would prove to be very important 5 years later, as you’ll learn if you’re still reading this and if you’re going to get through the rest of this post :D

July-August 2014: Lua sandboxing

The exploits were still rampant on the platform. One thing that would be good to emphasize here for people unfamiliar with Roblox is that not only did we have a full Lua interpreter based on Lua 5.1 (so pretty easy to reverse engineer as that is open source), but we also had a client-trusting networking model that was used in all games at the time. In the beginning of 2014 we introduced a new networking model which eventually (in 2018) became the only one.

People who are networking experts might scoff at this point. “Client authority is such an obvious mistake, what were they thinking?” To which I would say that it’s my firm belief that has Roblox started with a server-authoritative model, it’s very possible that the company would not exist today - it’s hard to develop multiplayer games, and client authority makes a lot of responsive gameplay very easy to write (of course it’s very exploitable, which is why we ultimately got rid of the old model, but at the time we already had lots of developers with years of experience, and also a much better understanding of how to make the platform more accessible despite the replication barrier).

Anyhow, the dominant attack vector in 2014 was to find a way where the script source, replicated from the server, gets to the client and replace it with a malicious script - which would get access to all our APIs and through the client authority allow to perform any changes to the world state.

With a secure replication mode being out but not being used by the majority of existing games, we had to find other ways to block these attacks but were tired of playing the cat & mouse game. To that end I reworked the Lua VM to split the compiler, removing it from the client completely (and switching replication to bytecode), and changing the bytecode to be different from stock Lua VM as well as changing the VM internals to obfuscate various data structures. This was hard to deploy - this breaks network replication for one - and we wanted to do this very quickly; this was also incompatible with some things like dynamic script evaluation, and even the process of starting a Roblox game involved downloading a Lua script from a web endpoint and running it! I focused on the core VM portions of this change and had another engineer help with other bits, and we ultimately shipped this change in around two months.

I remember reading the exploiter forums the night of the release, and seeing a thread to the effect of “all exploits no longer work”, and one of the exploit authors replying something to the effect of “oh god, this will take a while to get around”. Of course exploiters always catch up, and they did - months and months later (and we were able to continue playing the cat & mouse game for a while longer, until the replication mode became the de-facto standard).

September-November 2014: Smooth terrain

With Lua work out of the way, I went back to the hack week project from 2013. We had conversations earlier in the year and all agreed that we need a new terrain system - the old blocky one continued to not be very popular and we just didn’t believe that the features it provides are that interesting. With an existence proof from hack week, it was now time to figure out what to do.

I think this work started a bit earlier in the year in a separate prototyping framework where I was able to quickly experiment with voxel representation etc, but it was time to figure out how to ship this.

In September I’ve done most of the basic rendering work, and then started to focus on other aspects. This was the first large cross-functional project that I’ve done at Roblox - except for the terrain tools that were written by stickmasterluke, I’ve done all of the implementation work here.

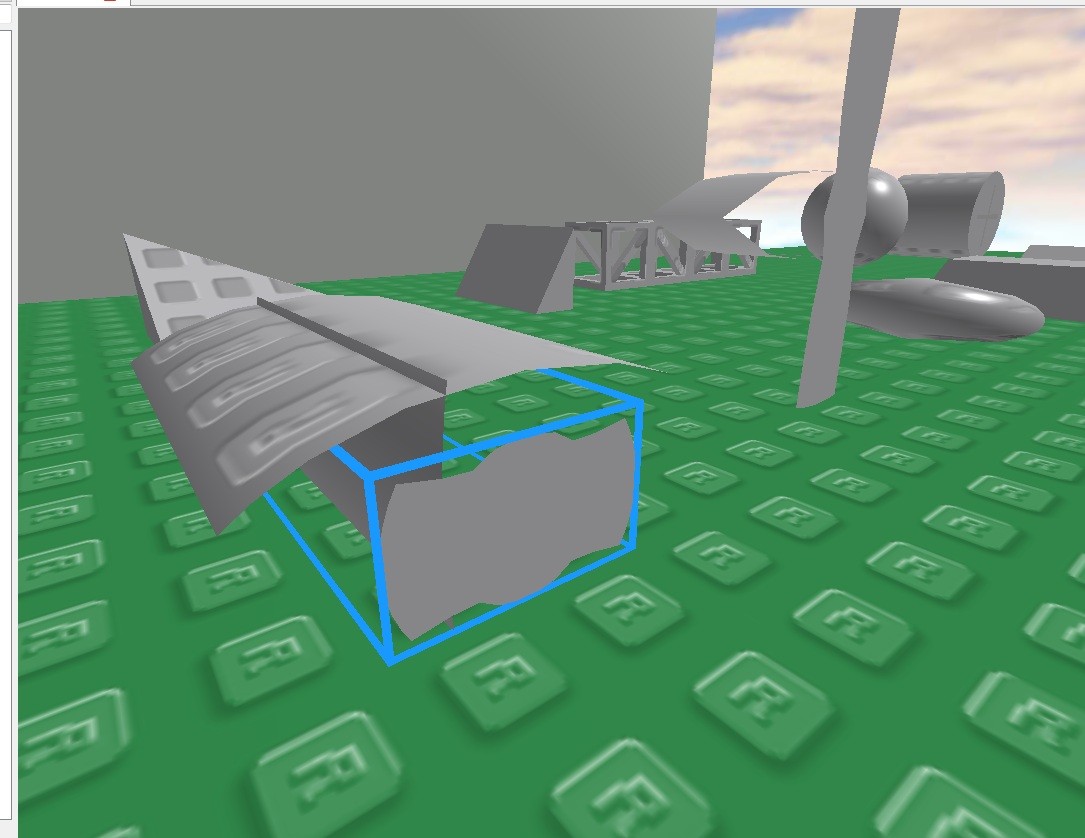

In October I’ve worked on physics - this was my chance to go back to some physics programming (I’ve done physics work in prior jobs, including a custom Box2D SPU port with many algorithms optimized or rewritten, but never in Roblox). This required using parts of Bullet collision pipeline which we’ve integrated earlier for CSG to work.

In November I’ve worked on some more rendering pieces and the undo stack, and started working on replication support. Again, a lot of this work was easier to do since it mirrored the Infinite terrain work from 2013.

December 2014: Hack week

I don’t remember my exact train of thought here, but I think I just accumulated a bunch of rendering ideas that I wanted to try; unlike my last hack week this one didn’t really have a specific focus, and I decided to just implement as many small ideas as I could possibly fit in a week.

A great side effect of this is that you’re always ready to present. This is a big challenge in hack week - how do you time things so that after a very intensive week of work you have code that works enough for you to show a demo? This being hack week, this code doesn’t have to work perfectly - in fact you want to minimize the amount of “polish” work you do so that you can maximize the “oomph” and deliver more ambitious projects - but what if you don’t make it? The way I solved this problem in 2014 is by cramming a bunch of small projects into one; every day I’d start with a goal of finishing one aspect, and if I got there earlier - great! Just start the next one early.

What ended up in the hack week presentation is area light support for the voxel engine (later shipped as SurfaceLights), encoding light direction into voxel grid for per-pixel lighting (never shipped, but incorporated into the next hack week), soft particles (shipped later), particle lighting (this was done in a very brute-force way in this demo; I implemented it in a better way in Future Is Bright hack week, and we shipped that implementation later), HDR rendering with a very poorly tuned tone mapper (we didn’t use any of this code but we did end up implementing HDR rendering as part of Future Is Bright), shadow mapping with support for translucency and colored objects based on exponential shadow maps (we didn’t ship this exact code but this will show up later in the timeline), and volumetric lighting support using the shadow maps (never shipped this either).

This hack week ended up being rich on small practical ideas - except for volumetric lighting and colored translucency, we ended up shipping all of these in one form or another over the next few years.

January 2015: Smooth terrain tools & API

With the hack week being over it was time to continue working on smooth terrain, bringing it closer to completion. Here we’ve tried to figure out how we should work on tools. Traditionally you’d expect the tools to be implemented in C++, but we wanted to give our plugin creators a lot of power.

So we decided to try to implement a fast Lua API for voxel reads and writes (bypassing our reflection layer for performance), and build tools in Lua on top of this. This ended up being a great decision, as we were able to quickly iterate on tools and have community be empowered to create their own (performance, of course, suffered as a result - something we’re trying to fully recover from to this day).

February-June 2015: Smooth terrain productizaton

At this point all the pieces were there - I had rendering, physics and replication working, and an API to build tools with. The tools weren’t ready yet, but neither were any of the pieces production quality - a lot of cleanup optimization work remained.

During these months I’ve worked on polishing the code and making it faster. This involved writing custom triangle mesh colliders instead of using Bullet code (using a fast cache coherent KDTree which was much faster to build and a faster to query compared to Bullet’s BVH), improving rendering code performance and memory consumption, improving terrain broadphase, making old APIs work with smooth terrain, etc., etc.

A lot of work goes into a high quality feature, and a lot of work can follow the first version - during this time I also prototyped geometric LOD support but it wasn’t ready for the release so we shipped without it.

During this time we also started replacing the old temporary art with new art, which required making some rendering changes to improve the look based on art feedback as well.

Overall I really loved working on smooth terrain. When a single feature touches so many areas, you get a chance to implement a lot of different things, get familiar with dark corners of most of the codebase, and improve a lot of code everywhere as a result. Smooth terrain also required innovation in the algorithms as well as a lot of attention to detail in performance to be practical, and resulted in an entirely new building primitive to be available for Roblox developers. Lots of people loved the result and as we continued working on performance (it was just me for the first couple of years but we had a few people work on impactful performance changes for terrain in 2019 and 2020 as well, sometimes coming up with much better solutions vs whatever I implemented in 2015), it quickly became a great way to build large worlds in Roblox. Of course sky (or, in this case, horizon) is the limit, and we need more and more improvements here.

I remember the week we shipped smooth terrain, and in the same week one of the biggest games at the time, The Quarry, switched to it - which was scary! I don’t think we were quite ready, and the feedback from players told us that the tech wasn’t quite optimized enough for big maps, but it was fun nonetheless.

July 2015: microprofiler

I don’t really remember exactly what prompted this, but I decided that the set of profiling tools we were using wasn’t really adequate for a lot of work that we needed to do. Instead of reinventing the wheel completely as I did in 2012, I decided to integrate a microprofile library by Jonas Meyer. I think I picked it over Remotery, which was the other open-source library available at the time, because Remotery required a web browser to work and I wanted something with on-screen visualization.

However, I wanted something that we could ship in the production client. Up until then if you had a performance problem in a non-development build the only hope of understanding what was wrong was to reproduce it on a local build and use platform-specific tools to profile. I wanted something where in any production build you could hit one button and instantly see the profiler you could interact with.

Getting there required a lot of fixes to the code to make it robust, to make it cheaper to compile the profiler code without keeping it active all the time, some features I felt were lacking, etc. All of this work was done in the open on GitHub (zeux/microprofile), but unfortunately the upstream repository at the time was hosted on Bitbucket and used Mercurial, which made pull requests impractical, and over time the fork diverged enough that it was too hard to merge it back. Ah well.

This ended up being possibly the single biggest thing I’ve done to improve internal engineering at Roblox. The culture of having the profiler at your fingertips, and having the same tool available on all platforms so that it’s always easy to check; the possibility to identify performance problems that are infrequent in nature; the fact that the same tool is available to our developer community so when they report performance bugs it’s now possible to get a profiler dump from them; all of these things made it much easier to talk about performance and to work on performance as a company. We also ended up shipping support for microprofile on the server (available to game developers, so that they can profile live servers with the same tool!), on mobile (again, used by us internally and game developers), and we also now have internal infrastructure to capture long running sessions and gather statistical information with ability to drill into individual problematic instances.

August 2015: Cylinders

Somehow at this point Roblox has existed for a decade with support for cylinder as a basic primitive type, but without physics support for cylinders (cylinders were “approximated” by a ball). During smooth terrain work I became familiar with our collision pipeline and it seemed straightforward to add cylinders by using Bullet support for cylinders - so I did!

This ended up causing a fair amount of trouble for our physics engineers, as they were later forced to fix several issues in Bullet integration (which is good, I guess) that became more prominent for quickly rotating cylinders, fix a few numerical instabilities in Bullet GJK that were important to make it possible to build cars with quickly rotating wheels, as well as reimplement ray casts that were very imprecise in Bullet as well.

Sorry about that, folks. But hey, at least we have cylinders now!

September 2015: Character shadows

Since before I joined and up until 2014 (or so?), we used stencil shadows for characters. Voxels weren’t small enough to represent a character with enough precision but stencil shadows were costly, painful to maintain, resulted in double shadowing artifacts and had a very different look from voxel shadows from the environment. We shipped blob shadows earlier - they solved most of these problems but were too coarse and didn’t look as good.

After my 2014 hack week I’ve tried to extend the exponential shadow implementation to be practical, but it was hard to make it work with only characters rendering into the shadow map, and I didn’t think we were quite ready for a full scene shadow map implementation. After several failed experiments I settled on a solution I liked, which was inspired by the static geometry shadows from the classical “Perspective Shadow Maps: Care and Feeding” article (written by the same friend who got me into Roblox - hi, Simon!), but incorporated an extra depth channel into the shadow map to be able to reject shadows from the surfaces that fail the test.

The trick is to have two-channel shadow maps where one channel stores depth and another stores the shadow intensity; then you blur the intensity and dilate the depth information, which allows you to render soft shadows very quickly, as long as self-shadowing doesn’t matter.

I later learned that the same technique is presented in GPU Pro 3 “Depth Rejected Gobo Shadows”.

Incidentally the doge meme was popular in Roblox at the time, so the ticket is appropriately named “US30615: Character Shadows Much Improved Such Wow”.

This shadowing technique remains in Roblox to this day, although it’s been largely superseded by the new exponential variance shadow map implementation that I contributed to by convincing the fantastic engineer who worked on this to try to make it work :D

October 2015: Various optimizations

I think at this point I was a bit tired of a few giant projects completed earlier in the year, and I just worked on a bunch of different small optimizations.

I find that this in general is a great way to spend the time between projects - if you wait for something big to ship, a fantastic way to deliver value is to open a profiler, look at a few captures, and try to make them faster by cleaning code up or using slightly more efficient constructions in the places that matter. In an engine such as ours, there’s so many games that stress parts of the engine in so many different ways, all of this work pays off eventually.

November 2015: OpenGL (ES) 3

I really don’t remember what this was motivated by. But up until this point we’ve used GL2 on macOS and GLES2 on iOS/Android. There was some important driver for adapting our code to be GL3 compatible, I just don’t remember what it was :)

This required some shader compiler tweaks and some code tweaks but ultimately wasn’t too bad. When I implemented the original GL backend I made the decision to make just one for all GL version, and I haven’t regretted this since (this was a direct response to OGRE having a separate backend for GLES which created many more problems than it solved).

Of course the hard part of this change came later. In December I had to work around a host of compatibility issues on Android and macOS, where older drivers didn’t necessarily implement GL/GLES3 correctly, requiring us to detect these and fall back to GL2/GLES2.

November 2015: Terrain memory optimization

This was always known to become necessary at some point, but we shipped the first version without it. During some memory analysis it turned out that smooth terrain was much more memory hungry than old blocky terrain. The ultimate solution to this was going to be level of detail, but it never hurts to make things more efficient - I switched to a carefully packed vertex format to reduce memory use, getting the vertex down to ~20 bytes. In addition a bug in the old code generated ~10% vertices on the border of chunks that just weren’t used, so that was one more easy win.

December 2015: Hack week

So this year, unlike last year but like the year before that, I had a theme. I knew what I wanted to do.

When we worked on the first version of the voxel lighting engine, we actually did a quick test to see what would happen if voxels were 1x1x1 stud. And the results looked fantastic. In the previous hack week I’ve also learned that we really need HDR, and that adding lighting direction to a voxel could make things look nicer.

I wanted to combine all of that and have a version of our voxel lighting that supported 1x1x1 voxels. If done naively, that requires 64x more memory - so I knew I needed many voxel grids, nested in a cascade. Even with that though, to maintain realtime updates for high resolution portion of the grid next to the player, you need way more power - so I knew I needed a GPU implementation.

At this point I’ve never written a compute shader, so doing all of this in a week was daunting. So - I confess! - I cheated by starting to work on the hack week 3 days earlier. Hey, don’t judge me - we didn’t even have support for compute shaders at the time!

What followed was 10 days of what probably was one of the most intense and fun rendering projects I’ve done. It wasn’t just working on lighting - it was working on a non-traditional lighting system using GPUs as a general purpose compute unit (given that I haven’t used compute shaders before…). And I had to get to a point where something worked in slightly more than a week.

I knew what I wanted to accomplish, but I didn’t know all the algorithms involved - I couldn’t simply port the CPU voxel lighting engine since a lot of that code can’t be parallelized to the point where GPUs can run that performantly.

So I had to reimagine some of the algorithms, use some technology… creatively… (e.g. the GPU voxelizer used instancing and geometry shaders to run the coverage shader for each voxel of the primitive’s bounding box, and then used max blending - I think? - to aggregate coverage per voxel in a 3D texture), and ultimately got to a demo a day earlier so I even had time to implement a really bad voxel GI using something resembling light propagation volumes (… trying to debug SH math in the process).

My biggest worry was that I would have nothing to show at the end. I didn’t have a working GPU debugger, and this was a very unfamiliar territory for me since I had to quickly get up to speed on what’s possible and what’s not possible in D3D11 compute. I remember being very dismayed at the D3D11 restriction around typed loads, and having to work around that.

In the end, I did get to a demo, and it was a blast.

January-April 2016: We Are VR

With the hack week over (but not done, as we’ll see later), I switched to the next big thing. This was the time when the industry was going crazy in a wave of VR. VR was the next big thing, it was happening, and it was happening now. Analysts were projecting explosive growth, and we knew we had to be there.

Well, we knew it would take years for VR to become pivotal, but we thought that by investing into VR now - by “getting on the map” - we’d secure enough foothold to become a strong player. To reduce risk, we decided to start with desktop VR - the plan being to add VR support to the platform and to use side loading to support Oculus and Vive headsets, without committing to any single store yet.

I worked on the engine parts of this initiative, adding support for stereo rendering, vsynced presentation, latency optimizations for parts of the input pipeline, integration of LibOVR and OpenVR, etc. We had a few other people starting to prototype character navigation, UI integration and the like.

Of course we had our fair share of rendering tweaks we needed to do - what do you do with particles? Do post-effects work? Do all parts of rendering code handle asymmetric frustums? Etc. As for optimizations, some of them were VR-specific and allowed doing something once per frame instead of twice, but some were general enough to apply to the rest of the rendering modes as well.

We also had to figure out a compatibility strategy - how do you play existing Roblox games in VR? We believed that this is where the strength of our platform lies - VR desperately needed content and we had a lot of it, it just wasn’t VR-ready. Which is why built-in character navigation and UI portability were a big deal - how do we do this with acceptable comfort? Games that wanted to could of course use VR in a more conscious manner; I remember building a table tennis simulator game that wasn’t very fun but it was still very profoundly impressive when you played it for the first time.

Once the desktop version worked, and we agreed we’d ship it in a stealth way, we needed to figure out what the full product release would look like. And, us being mobile first, we naturally turned to mobile VR.

From the business perspective this was a mistake, as mobile VR at the time was in a very sad state which we started discovering along the way; VR without positional tracking is not for the faint of heart, and the state of the ecosystem at the time was… bad. However this was also fun to navigate - we looked into Cardboard-like devices and, quickly getting dissatisfied with the SDKs available to us, I wrote a custom VR renderer using gyro/accel inputs, a pseudo Kalman filter tuned for latency, and a late latching setup where the final postprocessing quad would get timewarped using the latest known information from the CPU side about where the head is looking. The results were much better than what stock SDK provided, but still very far from a decent VR experience, let alone what you could get on desktop with positional tracking.

Except for the mobile VR code which never shipped, all the rest is still in Roblox today. Miraculously, it still works even though we don’t spend almost any time on maintaining it - in fact, one of the winners of a 2020 Game Jam was a VR game (The Eyes of Providence) that was actually lots of fun to play, with gameplay that was very unique to both VR and our platform and combined the strengths of both in one package.

Ultimately, we ended up testing the Daydream waters as well but never shipped anything - the engine still supports VR but a full product integration will have to wait for a time where a VR platform is meaningful to us as a business.

May-July 2016: Smooth terrain LOD

We always knew we needed a geometric LOD system for terrain. I even prototyped it when working on terrain initially, but didn’t have time to get it to work well enough to ship.

Well, now was the time. There’s a lot of careful work here in getting LOD updates to be responsive, managing the cost of geometry updates (which previously was limited to load time), hiding seams between chunks of different detail levels, etc., etc.

To test this I’ve used a level with ~500M voxels that was a Mars terrain import; levels of that size were only practical with LOD, but also stressed all other parts of the system, forcing me to implement a new in-memory storage format for voxel data, optimize various parts of the system, including deserialization, undo history and physics, and do more performance work everywhere.

Even that proved to not ultimately be enough, and we had a few more people take a stab at improving various components of the system since.

August 2016: New shader pipeline

With an eye towards new features, such as compute, and new graphics APIs, such as Metal, I’ve set out to find a better solution for shader translation. The combination of hlsl2glsl + glsl-optimizer worked but was limited to DX9/GLES2 style shaders, and everything else was a hack.

One thing I’ve wanted is support for constant buffers, which would clean up the way how we handled constants in the cross-platform rendering abstraction a lot, but it was very painful to do.

So I set out to find a new solution, and settled on hlslparser, as used in The Witness. It was using an AST->source translation which was simpler than our previous pipeline, e.g. for Metal we wouldn’t have to go through glsl-optimizer’s IR, but it was incomplete so I ended up working on a lot of small changes to make it practical to switch to it (all of them are merged upstream), and replacing our old pipeline. We still relied on glsl-optimizer for OpenGL to optimize the shaders as that made mobile drivers happier, but this opened the door to using more modern features, such as uniform buffers, in the “frontend” (hlslparser could then flatten these to vec4 arrays, which made the resulting shaders compatible with ES2).

Thus the second version of the shader toolchain got born; we will end up reworking this again in the future!

September 2016: Rendering abstraction cleanup

Before implementing Metal support, I’ve wanted to make it easier to implement more modern APIs. This involved reworking the constant handling - we used to use integer handles that could be retrieved by name, like in GL - and introducing render pass support.

For constants, we settled on constant buffer support, where a structure layout is mirrored between CPU & GPU, and the entire buffer is set in bulk. This ended up being a huge win both in terms of simplicity of the code and in terms of performance - up until that point we’ve had to emulate constant buffers on Direct3D 11 (which was a port done by another engineer which is why it wasn’t mentioned in this post), and set individual uniforms on GL. With this change we had the shader compiler flatten the uniform structs into vec4 arrays for GL, and we could remove all reflection code from our shader pipeline, and simplify and optimize the setup significantly.

For render passes, we were targeting Metal so we went with a simple immediate-mode pass specification. It is used by our high-level rendering code with explicit load/store masks, and used in GL backend to discard attachment contents when necessary.

This is also the large significant refactor of our rendering interface; today, almost 4 years later, it looks pretty close to how it looked like 4 years ago - which is nice! I think we found a great balance between simplicity and performance across all the different APIs. The only large addition since then was support for compute, which we still aren’t using in production [but it helps on hack weeks…].

October 2016: Metal on iOS

With shader translation support implemented by hlslparser and the rendering abstraction refactor done, it was time to do a Metal port. The motivation was, of course, render dispatch performance - GL driver consumed a significant portion of our frame, for what didn’t seem like a good reason.

I think I did the initial bringup on a Friday. I came to work a bit early, wrote code non-stop until 6 PM, went back home, and proceeded to write code until 10 PM when the app ran and rendered correctly.

Of course after that I had to spend the rest of the month on cleanup, corner case fixes, optimizations, etc., doing some small refactoring in other backends to make implementations align closer.

Metal worked very well after that - on iOS we had very few stability issues after launch, and the backend required little maintenance since.

November 2016: Assorted cleanup and optimization

It doesn’t look like anything very big happened here - some small cleanup of the rendering backend, some leftover Metal fixes, optimizations, etc.

Calm before the storm, as they say.

December 2016: Hack week

Was it possible to top the last hack week?

I felt like the demo from the last week, while very awesome technically, didn’t quite have enough ‘oomph’. Part of the problem was the limitation of the voxel lighting technique, so I wanted to fix that, but also to have a slightly less ambitious plan.

This may come as a surprise because the result of the hack week was what probably is regarded by the community as the best thing I’ve ever worked on:

However something to realize is that in the previous year, I was stepping on untrodden ground; this year I decided to see if I could implement a production grade lighting engine - while pretty much knowing exactly what I need to do and how. I’ve implemented shadow maps many times before in my life; I’ve even implemented a Forward+ renderer in my F# engine (as you probably realized from the lack of F# in the few years of updates, I stopped using the language for a while) a few years ago.

I just needed to combine all of that. In addition I think this was right after reading a slide deck on Doom 2016 - which is a game that looks great, is very fast and has a very simple renderer by modern standards. I was inspired by this and decided to implement that - Forward+ with shadow maps, and Doom 2016-style particle lighting with an atlas.

I think I didn’t cheat this time around, I probably started the hack week on Saturday but that seems fair (?), and I managed to implement the entire thing in a week. It helped that I already had decent HDR code from last hack week so I could copy that, I had compute scaffolding so I could copy that for the light culling; the rest had to be mostly done from scratch, except for the light culling shader that I stole from my F# engine.

The results, well, the results shaped the Roblox lighting work for the next 3 years. We ended up sharing a build with the community and developers made levels that blew our minds.

2017: Future Is Bright and Vulkan

I think I’ve been writing this blog for 4 hours now and I’m not even up to 2020. But the interesting part is that it looks like in 2017 I’ve done very little work that actually shipped to production in a meaningful way.

This is because of a few things coinciding.

One, I’ve started doing way more technical direction. Helping teams with the roadmaps, helping design solutions to some hard problems, doing code reviews, etc. etc. This was also the time when I was the de-facto rendering team lead which didn’t reflect well on the time to write code.

Two, a lot of my attention was spent on the Future Is Bright prototypes. I now had two hack weeks from two prior years, both had very interesting ideas but we needed to figure out which one of them, or which combination of ideas rather, we need to pursue. This was more tricky than you’d think - some people in the company favored the voxel approach for reasons I won’t go too much into, and the voxel approach resulted in very unique soft look, and provided an answer to the entire rendering equation; shadow map approach resulted in superior quality for direct lighting, and was faster, but wasn’t sufficient by itself.

We also needed to answer content compatibility questions (what do we do on low end?), among others.

So I ended up doing a lot of research/prototype work on both implementations, trying to find the limits of both approaches. This resulted in more explorations into GPU-friendly ways to do voxel lighting, adding extra features, ultimately porting both prototypes to Metal and running them on an iPhone, etc.

The summary of this work is available here. We eventually decided to pursue the shadow map/forward+ route for direct lighting, and are likely going to use a voxel-based solution for the indirect components in the future.

Three, Vulkan was the next API to tackle. The final boss, so to speak. Another engineer did the initial port but eventually I took over.

The concrete projects that ended up shipping involved more work on the rendering API (adding compute support to make next hack weeks easier…), and building a third - hopefully final! - version of the shader compilation pipeline using SPIRV, a shader intermediate representation from Vulkan. This included contributing to multiple open-source projects to make this practical, a lot of work I won’t go into since I’m getting tired writing all of this.

At the end of the year we settled the FIB path and had a Vulkan implementation that was ready to ship on Android - or so we thought. The real release had to wait until next year.

Of course throughout the year I shipped a few small optimizations here and there and worked on a few fixes.

May 2017: Memory tracking

… oh, and there’s this. We were working on some memory diagnostic tools and I decided to see if I could implement a very low-overhead always-on tracking system for memory.

To make this practical, it had to be able to categorize memory allocations but do nothing else - by overriding global operators new & delete and embedding a little bit of metadata in addition to the user data, it was possible to do this at minimum cost and keep it enabled in all builds.

This ended up challenging to do well because of various issues with allocator mismatch, and required some further work in 2018, but the system does exist to this day and remains a vital source of memory-related information in production builds.

We had a few people look at memory occasionally, but it always involved using somewhat clunky platform-specific tools and made it a bit hard to tell at a glance whether there’s a problem. Now that we had a way to validate memory usage and identify biggest consumers to trigger a subsequent investigation, a few memory-related issues became obvious. So I also worked on fixing some of them, including some mesh memory optimizations (using my independently developed library, meshoptimizer), reducing script bytecode size by compressing it better, coming up with a new encoding scheme for part outline data which helped us save 20% of part memory - two years later I removed outlines from our code outright as they weren’t useful any more, but back then we still had games relying on them - and fix a few assorted memory problems with animations.

January-February 2018: Vulkan

In the beginning of the year we basically had rock-solid Vulkan code, but production deployments required working around lots of driver issues and there wasn’t enough time for that, so that work had to happen in 2018. In the first couple of months we ironed out all of the issues and finally activated Vulkan on a large subset of production devices.

More fixes were required throughout the rest of the year. Vulkan proved extremely challenging to fully release - I’m happy that we did do this now, with 60% of our user base using that and enjoying the resulting performance benefits, and it providing a path to us not relying on OpenGL as much; but it was a struggle, and honestly to a large extent it’s stubbornness and sunken cost fallacy that got us over the milestone.

I’ve written enough about Vulkan elsewhere, between multiple talks at different conferences and a few blog posts here so I’ll just leave it at that. I take equal amounts of pride and solace in me, among other early adopters, paving the way for others to have an easier time.

February-March 2018: Network performance and bandwidth

One side effect of Vulkan work is that it got me completely burned out on rendering. I suspect it’s a combination of this just being incredibly frustrating, and - along with lighting prototyping - contributing to me not shipping anything concrete in 2017. So I felt like I was done with rendering for a while, and while I still helped guide the team to deliver other projects, I wanted to do other things for a change.

Partly because of this and partly because of some challenges in this area at the time I took a brief detour to focus on networking. As part of this I’ve implemented many small performance fixes to various parts of the stack, redesigned parts of the networking protocol to be more efficient, completely rewrote our physics data compressor to provide higher quality with less bandwidth consumption (this code is still used today, although it’s possible to improve on this further), and wrote a few specs for future improvements in this area, most of which have been implemented by other people now.

March 2018: Hack Week

I forget why, but the hack week didn’t happen in 2017 and happened in March. According to what I wrote above I was pretty done with rendering, and decided to do something else. At the time I have spent a lot of time thinking about the future of scripting at Roblox - programming languages and evolution thereof.

To that end I’ve decided to explore a set of static typing extensions over Lua, using my script analysis work from 2014 (which we’ve used since it shipped) as a starting point. I extended the syntax with optional type annotation, and wrote a hybrid between a data flow analyzer and a unification-based inference engine, which you can see in action here:

We haven’t used any of this code directly but this paved the way to a lot of the subsequent programming languages work we’ve started doing, although I personally haven’t worked on the type checking bits too much - see below!

April 2018: Accurate Play Solo

As I was working more on networking code, I started to understand the limitations and flexibility there very well. At the time Studio had a Play Solo testing mode that wasn’t using replication; it was a constant struggle to keep your game functioning correctly because of the semantics differences.

This would come up in discussions occasionally and everybody either said that we really need the play solo mode because anything else just can’t be fast enough, or that we really need a full, if slow, replicated cloud-based testing solution as that’s the only way to get parity with production. At some point I couldn’t take it anymore and I just went ahead and built a prototype that started a full replicated session locally very quickly.

For this to work I had to tweak a bunch of parameters in the networking code and, crucially, spawn the server and client in the same process, so that it could happen as quickly as possible. There was still more overhead in this mode, and you did need two full datamodels, but it was much better than anything else we had and so we decided to ship this. I only worked on the initial prototype here, but the important lesson here is that existence proof is so often so important - the best way to get people to believe something is possible is to show the fait accompli to them and watch them marvel.

Since then we’ve removed the old play solo from the product, although there are some parts of the play solo flow that aren’t as fast as my old prototype was - which we will fix one day.

July 2018: New terrain rasterizer for pathfinding

(note, I’m omitting some more shader pipeline work and background Vulkan work in prior months)

Generally I think I was still in the mode of helping others much more than doing personal work in 2018. A few highlights from these projects involve me rewriting the rasterizer for navmesh generation, and dynamic instancing for rendering.

In June or thereabouts one of our engineers was finishing the rewrite of the navigation system, from the old voxel-based system to the new system based on Recast+Detours. Part of the system involved voxelization into spans and using the result to generate navmesh.

The rasterizer used in that system is conservative, and not that efficient; on large maps with a lot of terrain this was proving to be a bottleneck. I realized that due to the somewhat unique construction of the terrain mesh it was possible to do a very good approximation using a fast non-conservative half-space rasterizer, and use a few tricks to match positive triangles to negative triangles to fill spans very efficiently.

Curiously, even though I’ve never worked on any commercial products that targeted systems without a GPU, this is the second software rasterizer I ended up shipping - the first being one for a software occlusion system running on the SPUs back in my PS3 days.

July 2018: Cross-cluster instancing

Another engineer was finishing the instancing system; despite this being a rendering project I couldn’t resist and looked into improving performance of that code, and ended up adding dynamic instancing in addition to clustered batched instancing.

As a result, we have a system now that can aggregate large sets of similar objects statically so that we don’t waste the time to regenerate and reupload constant data for heavy scenes, but if some sets are smaller, we reaggregate them dynamically on the fly to merge the resulting draw calls for free.

The result is performant almost regardless of the scene composition which is neat!

November 2018: Help optimize FIB phase 1

Other folks were actively working on FIB phase 1 (which consisted of a new voxel lighting implementation with HDR support, a tone mapper and an HDR-ish postfx pipeline), but in November we realized that we aren’t sure we can make it by the end of the year - the code was done, it worked properly, but we wanted to ship with minimal performance regressions and our metrics showed us that were we to ship now, we would have dropped performance by 10-15% on mobile.

So I helped by implementing a few optimizations in various places of the stack to get us back on track, which contributed to helping release FIB phase 1 on time.

The rest of 2018 doesn’t seem super eventful - similar to 2017, I’ve worked on a few small bits here and there and focused a lot on helping others, writing specs, that sort of thing. Until at the end of 2018 I wrote a technical spec for the next Lua VM which would consume much of the next year for me.

Aside: Future of FIB

In some sense of course Future Is Bright is my child. I made the original hack week demo, and was very involved in the initial stages of the production work, including some fixes for phase 1 above.

However, the other phases see progressively less of my involvement, and all phases would not have shipped without other people’s work. In fact despite my original code still being present in all three phases, most of the code in all three phases is not mine.

I was somewhat involved in the phase 2, not so much by contributing code, but by convincing the engineer who did a lot of the work to try to figure out how to combine a few crazy ideas we were discussing together, notably tile-based incremental cascade updates (inspired by Insomniac’s CSM Scrolling) with EVSM (exponential variance shadow maps) - look ma, no PCF! This ended up working wonderfully even though it was daunting at first.

As far as phase 3 is concerned, although some of that code is still the same as it was in my hack week, again most of the effort at this point is not mine. As Roblox grows and I take more of an advisory role in rendering, more and more the work we ship is that of the entire team and a lot of different engineers Roblox developers may or may not know, as opposed to a few people who started all of this.

2019: Luau

At this point I knew pretty much exactly what we need to do in terms of language evolution at Roblox. We used Lua 5.1 as a base, but it wasn’t fast enough - so we needed a much faster implementation - and it wasn’t robust enough for large projects, so we needed gradual typing.

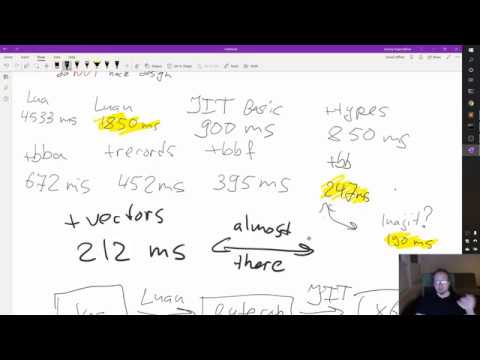

One engineer started working on the type system, and I started working on the virtual machine. We took the existing linting infrastucture I wrote in 2014, took the parser from it, made it more robust and faster, and then I wrote a compiler that compiled it to the new bytecode, an interpreter for this bytecode, many changes in the VM to make faster execution practical, etc.

This would consume me for the entire year, in addition to guidance for other projects in the company. It’s by no means a trivial task - I ended up delving very deeply into the dark art of making fast interpreters, tuning ours tightly to the compilers and hardware we ran on, making a lot of performance improvements everywhere in the Lua stack (e.g. our reflection layer, even though not being part of the system, ended up being 2-3x faster as a result of this work - once you have good benchmarks, it’s easier to make progress!).

This represented more than just making things faster though - it’s a new chapter in Roblox history, where before this we used the language we’ve been given since the very beginning, and now we treat it as our own, Luau. This resulted in us adding libraries we could have technically added before but due to the lack of focus haven’t, adding features that the Lua community at large has been begging for for years but that somehow never made it to Lua proper, and in general doing a lot of deep, meaningful and impactful work that helped our community.