Optimal grid rendering isn't optimal

31 Jul 2017I have been working a lot on vertex cache optimization lately, exploring several algorithms from multiple axes - optimization performance, optimization efficiency, corner cases and the like. While doing so, I’ve implemented a program to verify that the algorithms actually produce results beneficial for real hardware - and today we will discuss one such algorithm, namely “Optimal Grid Rendering”.

Vertex cache

First, let’s very briefly cover what vertex cache stands for. It has many names - post-T&L cache (from the days of fixed function hardware), post-transform cache, parameter cache and probably a few others I don’t know about. What it amounts to is that GPU caches the result of vertex shader invocation - namely, all the output attributes - in a cache that’s keyed by the vertex index and is usually small (tens of vertices). If the vertex index is not found in the cache, GPU has to run the vertex shader and store the results in this cache for future use.

The details of cache behavior are not documented by GPU vendors to my knowledge, and can vary in terms of the size (does the cache store a fixed number of vertices? fixed number of vector vertex shader outputs? fixed number of scalar vertex shader outputs?), replacement policy (FIFO? LRU?) and some other aspects (interaction between vertex reuse and warp packing). However ultimately the efficiency of the cache depends on the order of vertex indices in the input index buffer.

There are several algorithms that optimize meshes for vertex cache. Some of them model a cache with a specific size and replacement policy, others use heuristics to produce cache oblivious meshes. Generally these algorithms operate on generic triangle meshes, but today we’ll look at an algorithm that works only on uniform grids.

Optimal Grid Rendering

Ignacio Castaño wrote a nice blog post about a technique that allows one to achieve perfect vertex cache hit ratio on a fixed size FIFO cache, called Optimal Grid Rendering. This technique is not new; it’s hard for me to date it precisely - I personally learned about it circa 2006, but I’m pretty sure it comes from the days of triangle strips and hardware T&L. The key parts of the algorithm are as follows:

- Rendering the grid as multiple vertical strips, with each strip width being just under the cache size;

- Prefetching the first row of each strip using degenerate triangles.

This algorithm is designed to have each vertex leave the cache at exactly the right moment when the vertex will not be needed again. Picking the right cache size is crucial - if you produce the optimal grid for a cache that’s slightly larger than the one target hardware uses, you get an index sequence that transforms each vertex twice (the same thing happens if your strips are correctly sized but you remove the degenerate triangles from the output).

Given a cache that is exactly the right size and uses sequential FIFO replacement policy (vertex indices are added to FIFO cache one at a time), the resulting sequence is perfect. The question is, does the actual hardware performance match this model?

Measuring vertex shader invocations

There are several ways to investigate the vertex reuse behavior on a given GPU for a given index sequence:

- Measure time it takes to render a mesh with the index buffer;

- Measure the number of vertex shader invocations directly using GPU performance counters;

- Measure the number of vertex shader invocations indirectly by using atomic increment in vertex shader.

Ultimately we care about the time it takes to render, but it’s hard to measure time in a stable way, especially on a GPU. We could setup a contrived workload with an extremely heavy vertex shader to make results more accurate, but we’ll do something else.

Both other methods can be faulty as well - GPU performance counters don’t necessarily have to return sensible information, and driver could change the execution flow based on whether vertex shader has memory writes (for example by disabling vertex reuse…). However for the sake of this analysis we will use the performance counters, which can be read using D3D11_QUERY_PIPELINE_STATISTICS.

So our testing method is as follows:

- Render the mesh using the supplied index buffer

- Use pipeline statistics query to get the number of vertex shader invocations

- Confirm the pipeline statistics data by comparing the number of triangles with the expected baseline

Algorithm evaluation

We have several algorithms we will evaluate:

- Optimal - Optimal Grid Rendering algorithm described in the aforementioned article, with striped data and row prefetching

- Striped - render the grid as striped columns but do not render any degenerate triangles for prefetching

- Tipsify - take the regular uniform grid and optimize it for vertex cache using Tipsify algorithm

- TomF - take the regular uniform grid and optimize it for vertex cache using Tom Forsyth’s algorithm

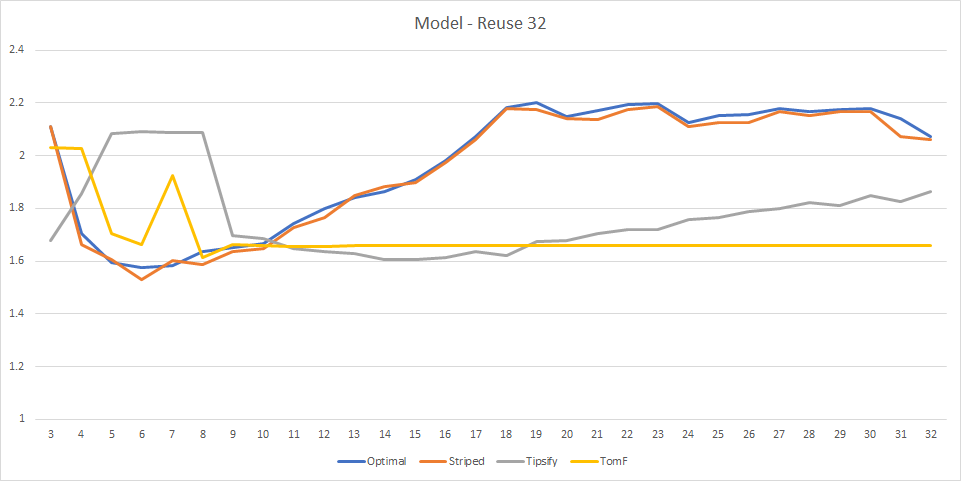

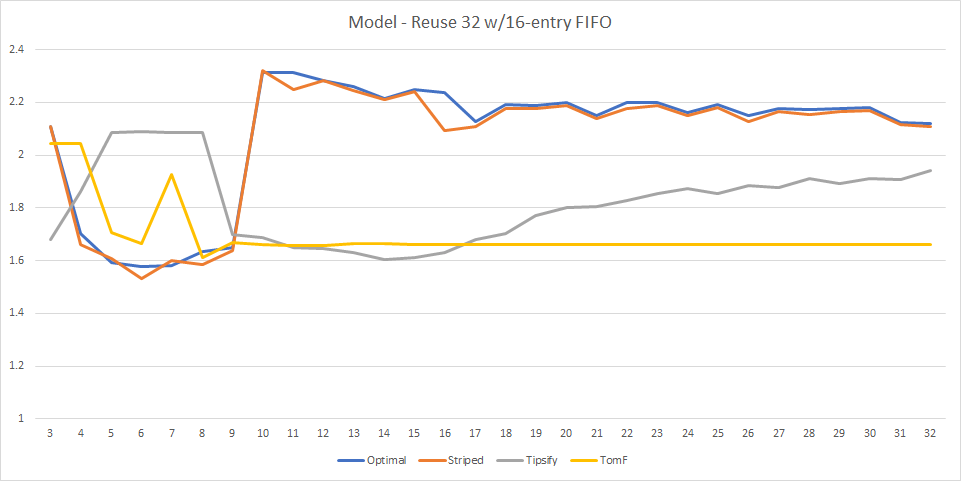

For evaluation we will compare ATVR - average transformed vertex ratio, or the ratio of vertex shader invocations to total number of vertices. The ideal number is 1 - based on the Optimal Grid article, we would expect Optimal algorithm to reach the optimum when the target cache size is set to hardware cache size; striped algorithm can only be effective when two rows of a strip fit into the cache, and should deteriorate to ATVR=2 for larger strips; Tipsify produces results depending on the target cache size and should produce results somewhat inferior to the optimal algorithm for the hardware cache size; finally, TomF should give the same results regardless of the target cache size.

For each GPU we test, we will look at a graph of ATVR (lower is better) for all 4 methods based on the cache size, for a 100x100 quad grid. Traditionally the cache size is measured in vertices; while it’s possible that the number of attributes vertex shader outputs affects the effective cache size, on all 3 GPUs that are tested there is no observable difference between having the vertex shader output 1 float4 attribute and 10 - as such all tests are done on a vertex shader that outputs 5 float4 attributes.

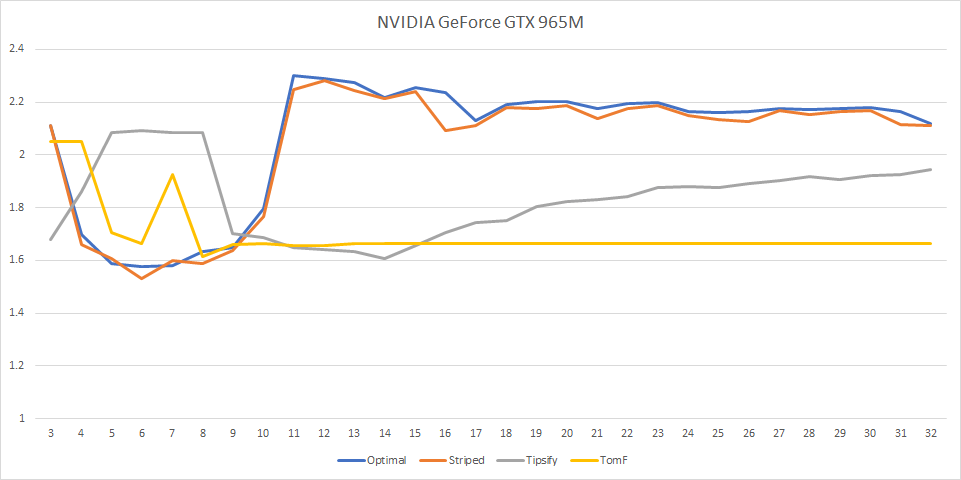

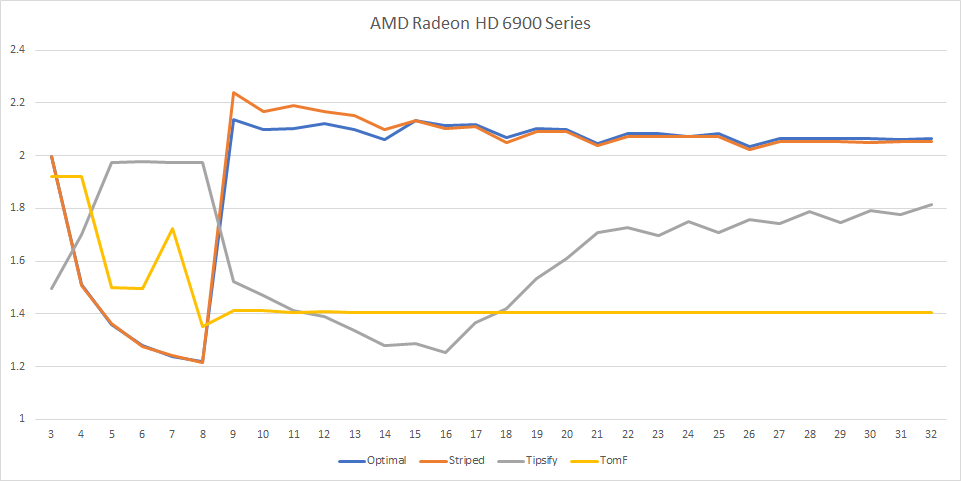

Results: NVidia and AMD

The results here are not what we’d expect.

For NVidia, the best method is Striped with cache size 6 (this results in strips that are 4 quads wide, or 5 vertices wide), with ATVR 1.53; Tipsify performs best at cache size 14 with ATVR 1.60; additionally, both striped and optimal reach ATVR >2 at cache size 11.

AMD has similar results - the optimal method is Striped with cache size 8 (ATVR 1.21), Tipsify peaks at cache size 16 (ATVR 1.25).

These results suggest that either the cache replacement policy is completely incompatible with Optimal Grid Rendering method, or that degenerate triangles are filtered out before the vertices get processed, or both.

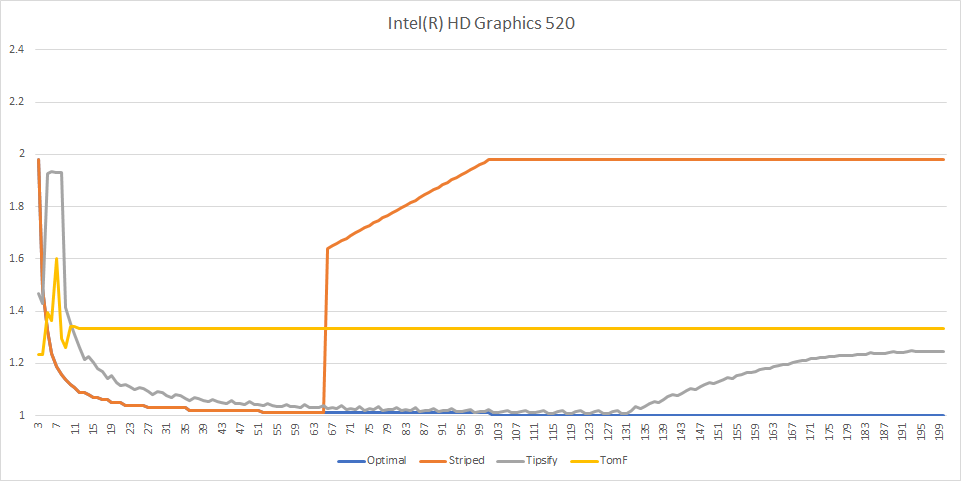

Results: Intel

These results are more in line with what we thought might happen - optimal reaches ATVR=1, striped breaks down for cache size 66 (strip size 65 vertices), Tipsify is slightly worse than optimal but approaches it at cache size 128 (ATVR 1.007). This suggests that Intel has a FIFO cache for 128 vertices, which actually means that with optimal grid, we don’t even need to stripe the 100x100 grid - one row of the grid fits into the cache as is.

Hypothesis: degenerate triangle prefetch doesn’t work

So while on Intel the algorithm clearly works, it doesn’t work on AMD or NVidia. The algorithm requires a FIFO cache and expects degenerate triangles to generate vertex shader invocations, so maybe degenerate triangles are skipped very early?

We can test whether degenerate triangles are filtered out by computing the number of invocations in a vertex buffer where some vertices are only referenced by degenerate triangles, such as this one:

0 1 1 2 3 4 5 5 5

For a GPU that feeds vertices in a degenerate triangle through the same vertex pipeline we’d expect 6 vertex shader invocations - and indeed this is what we get on all three GPUs. Thus this doesn’t seem like the problem here.

Hypothesis: cache uses LRU replacement policy

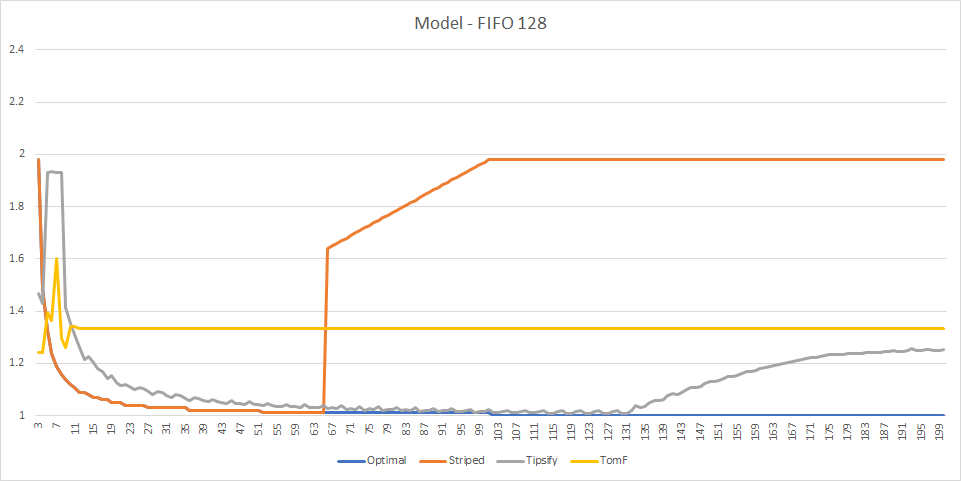

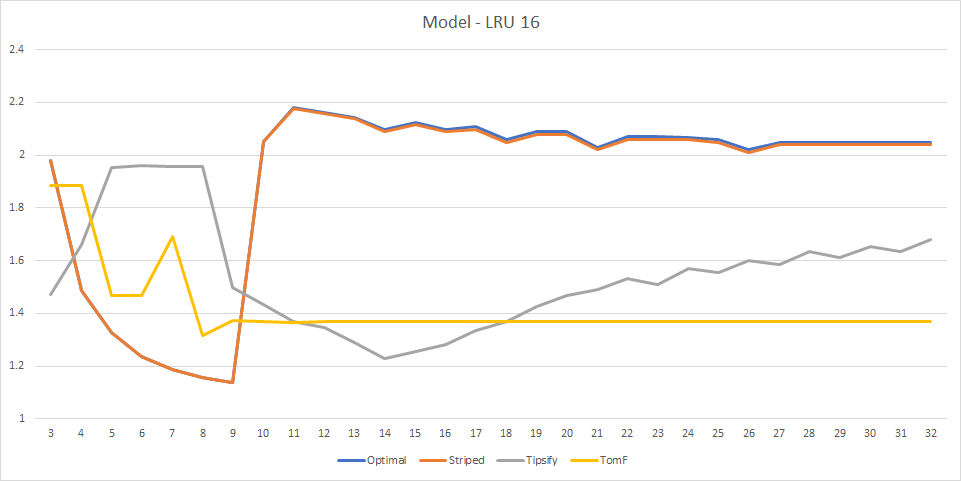

If AMD and NVidia do not use strict FIFO, what could they use? There are probably many algorithms one can use with many small tweaks, but one obvious alternative is LRU. It should be possible to learn how the cache works by inspecting the vertex shader invocations for a variety of index buffers, but let’s try something simpler - let’s model a FIFO cache with a fixed size and an LRU cache with a fixed size and see what results we get.

With a fixed size FIFO cache of 128 vertices, we are getting the exact same result we got from Intel GPU - which means that our guess was probably right.

With a fixed size LRU cache of 16 vertices, we are getting results that resemble both NVidia and AMD a lot in shape, although there are some deviations. The Tipsify curve matches NVidia curve for that algorithm, but AMD curve has a smaller minimum with a somewhat larger cache size (note that Tipsify simulates a FIFO cache as well, although it doesn’t take as much of a penalty for running the results on LRU cache of a similar size, so it makes sense that the sizes don’t quite match), as well as a slightly smaller optimal strip size.

Hypothesis: vertex reuse and warps

If you think about the GPU as a massively parallel unit, and take into account the fact that you need to dispatch warps with 32 vertices to compute units (or wavefronts with 64 vertices on AMD), the concept of a fixed size cache with vertices inserted into it one by one stops making sense. In the fantastic blog series “A trip through the graphics pipeline”, Fabian Giesen suggests an alternative way how the cache could work - in fact, it might be better to think of it as vertex reuse within warp instead of a cache.

Let’s say that primitive assembly submitted triangles to the rasterizer in the form of a warp id, and three indices into the warp. Then to achieve vertex reuse within the entire warp we just need to gather triangles for the rasterizer to process up until we fill up the entire warp worth of vertices to process. Then we would have up to 32 vertices in a warp referenced by some number of triangles in rasterizer; when the warp completes execution, we can kick off rasterization of all of them immediately.

It seems that we’d also want to kick off rasterization work in some limited batches; in case of an index buffer with repeating triangle 0 1 2 we’d have to buffer a lot of indices into the same warp - so it’s likely that the number of triangles we can dispatch is pretty small. By measuring the vertex shader invocations for the index buffer (0 1 2)+, it looked like on NVidia hardware specifically each subsequent batch of 32 triangles increases the vertex shader invocation count by 3, suggesting a buffer of 32 triangles.

While this model has some improvements over the LRU in terms of how well it matches the observed data (for example, it has the same saw tooth pattern for striped grid at small sizes), overall it’s actually worse than LRU - it does not degrade as quickly as real hardware when the grid is rendered using strips that are too wide. The data we have observed definitely suggests some smaller fixed size limit. Which brings us to the final question - what if comparing indices with the entire warp of data was too expensive, and instead we only compared to the last 16?

At this point we are in the land of guesswork - it could be LRU-within-warp or it could be some other limiting factor that I’m not accounting for instead; however this graph does look quite similar to the graph we get on NVidia hardware. If NVidia engineers ever publish the details of their vertex cache I will be glad to learn how wrong I was throughout the entire post ;)

Update: NVidia engineers didn’t, but in 2018 a paper Revisiting The Vertex Cache: Understanding and Optimizing Vertex Processing on the modern GPU was released which builds a more precise model of vertex cache behavior using somewhat similar techniques, along with a special purpose optimization algorithm.

Conclusion

We have gone through an interesting exercise of measuring the actual behavior of given index sequences on real hardware, and trying to model several possible approaches hardware could take to understand the behavior better. It’s pretty clear that Intel uses a 128-entry FIFO cache; as for AMD and NVidia, 16-entry LRU seems to approximate their behavior pretty well, although it’s doubtful that this is how the actual hardware works.

At any rate, neither NVidia nor AMD actually perform well using the Optimal Grid Rendering algorithm. This is a crucial lesson for the design of vertex cache optimization algorithms - it’s important that the algorithm does not assume the precise cache model. Ideally the algorithm would generate a cache oblivious sequence - in this case TomF’s algorithm tries to do that although you can see that it doesn’t perform very close to what’s achievable on the hardware - but even if the algorithm assumes a certain cache size, it would be best to treat the cache replacement model as a heuristic instead of a hard set of rules. Tipsify works pretty well on both NVidia and AMD - despite the fact that the algorithm assumes a fixed-size FIFO cache, it only uses the cache size for a heuristic to select the fan sequence, so when the model mismatches the performance remains reasonable.

You can get the source code used to generate data for the graphs in this post here.

| « Voxel terrain: storage | Voxel terrain: physics » |