qgrep internals

20 Apr 2019In 2011-2012 I worked on FIFA Street, followed by FIFA EURO 2012 DLC and finally FIFA 13 - all of these games were based on the same codebase, and this codebase was HUGE. Given an unknown codebase, you need a way to quickly get around it - since you don’t know the code, you resort to search-based navigation, aka grep. Using Visual Studio Ctrl+Shift+F search on a HDD on a codebase this size means that every search takes minutes. This was frustrating and as such I decided to solve this problem.

I wanted a tool that was much faster than existing alternatives1 and was able to perform both literal and regular expression searches at similar speed. At the time, the only existing tool that gave near-instantaneous results was Google Code Search - unfortunately, the performance on case-insensitive queries or some types of regular expressions at the time wasn’t very good2. Thus I decided to make a new tool, qgrep3. This article will go over the design and performance optimizations that make qgrep really fast.

How fast are we talking about?

Remember, qgrep was written in 2012, so the competition at the time was grep, ag, Visual Studio Ctrl+Shift+F, and the hardware target was a multi-core CPU with an HDD. Today the golden standard of performance is set by ripgrep, which runs much faster than the alternatives, and the norm is to use an SSD. Still, qgrep is much faster.

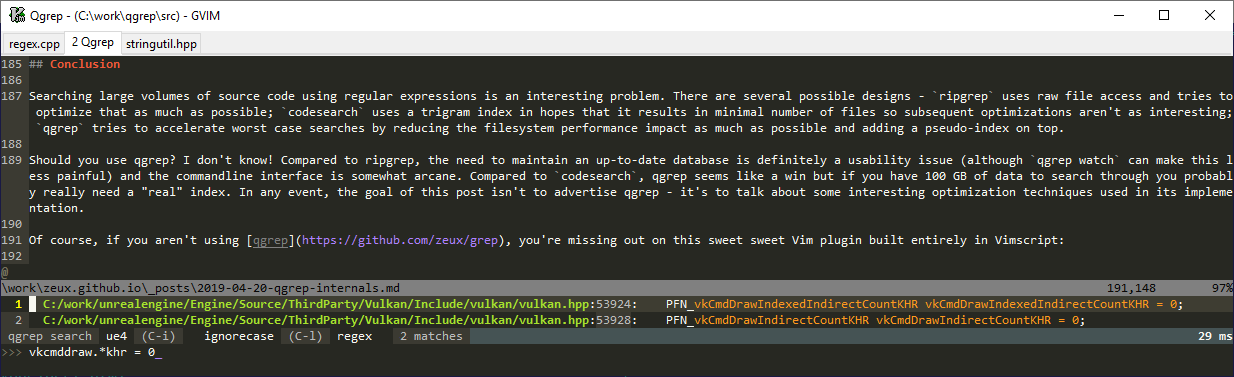

As an example, let’s try to search for a simple query, vkCmdDrawInde.*KHR = 0, in UE4 codebase which is similar in size today to FIFA codebase from 2012. We’ll run qgrep and ripgrep twice: first time is after a reboot so the filesystem cache is cold, and second time is immediately after that. The timings are done using my desktop system with i7 8700K (6 cores 12 threads) and Samsung 970 EVO SSD (which is an M.2 NVMe drive) on Windows 10, using latest ripgrep/qgrep x64 builds. Here’s the hot run:

C:\work\qgrep>build\Release_x64\qgrep search ue4 S "vkCmdDrawInde.*KHR = 0"

C:/work/unrealengine/Engine/Source/ThirdParty/Vulkan/Include/vulkan/vulkan.hpp:44478: PFN_vkCmdDrawIndexedIndirectCountKHR vkCmdDrawIndexedIndirectCountKHR = 0;

Search complete, found 1 matches in 0.03 sec

C:\work\unrealengine>rg --stats "vkCmdDrawInde.*KHR = 0"

Engine\Source\ThirdParty\Vulkan\Include\vulkan\vulkan.hpp

53924: PFN_vkCmdDrawIndexedIndirectCountKHR vkCmdDrawIndexedIndirectCountKHR = 0;

1 matches

1 matched lines

1 files contained matches

118457 files searched

143 bytes printed

1237500936 bytes searched

3.651454 seconds spent searching

1.216025 seconds

And here’s the table of timings in seconds; here we also run qgrep with a b option that will be explained later (it stands for bruteforce):

| tool | cold | hot |

|---|---|---|

| qgrep | 0.42 | 0.03 |

| qgrep bruteforce | 0.66 | 0.08 |

| ripgrep | 10.2 | 1.2 |

It’s possible that if in 2012 I used SSDs and ripgrep was available, I wouldn’t have gone through the trouble of making a new tool - but the pain threshold was crossed so I did and here we are. But how is it possible to make a code search tool that’s so much faster than ripgrep? Why, by cheating, of course.

Eliminating I/O bottlenecks

The single biggest source of performance issues at the time was disk I/O and I/O-related system calls. A recursive grep tool must start by recursively traversing the target folder; as new files are encountered, it needs to read their contents and perform regular or literal search on the results, and print the matches if any. In theory, the filesystem in-memory cache is supposed to make subsequent searches fast; on FIFA codebase, however, both file hierarchy and file contents was never fully in the filesystem cache, especially as you worked on the code (for example, switching to the browser to google something would likely evict large portions of the search data set). Even when filesystem hierarchy was in the cache, retrieving the hierarchy wasn’t very efficient either due to a large number of kernel operations required. As you can see by looking at ripgrep results, the impact is very significant even on SSDs; on HDDs we’re talking about waiting for a minute for the search to complete.

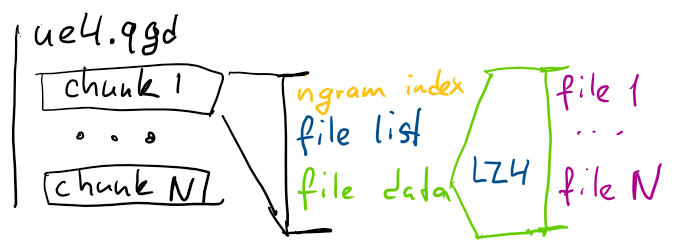

To get around these issues, qgrep maintains a compressed representation of the entire searchable codebase. It’s stored in one file that consists of chunks; each chunk contains a list of file paths and file data, both compressed using LZ4. Files are added to the current chunk up until the uncompressed size reaches a certain threshold (512 KB at the moment) and then the chunk is compressed and a new chunk is started. If a file is very large (which is actually the case for vulkan.hpp at 2.2 MB), it’s broken up into several chunks using newlines as a splitting point which works well because the search is line based.

Chunks are compressed and decompressed atomically in the sense that you can’t update just one file in the chunk - compressor receives a blob that consists of contents of all files concatenated together. Chunks that are too small decrease the efficiency of compression; chunks that are too large make incremental updates and parallel decompression less efficient.

Having a single file that contains compressed representation of all input data means that even if the file is not in the file cache, reading this is as fast as possible since it’s often stored contiguously on disk. Compression is important because HDD read speeds are pretty slow compared to fast decompressors, and compressing increases the chance the files will stay in cache.

One other big advantage is that files can be pre-filtered during indexing to eliminate files that are not interesting to search; qgrep by default includes most text files using file extension as a filter. This means that large folders with, say, build artifacts, only affect the time it takes to update the data, and don’t impact search performance. On UE4 example above, ripgrep looks through 1.2GB of file data, and qgrep only looks through 1.0GB (compressed to 212MB).

Why LZ4?

An important goal when choosing the compression algorithm was to have decompression run at similar performance to the search itself (which, as you will see soon, can be really efficient). While it may seem that having a slower decompressor is good enough as long as it’s much faster than the disk, when the file stays in cache the disk I/O isn’t a factor so the faster the decompressor is, the better.

At the time a solid choice for having extremely fast decompression performance was LZ4; today Zstd provides an interesting alternative that I haven’t evaluated rigorously for this use case. Snappy was an alternative available at the time but it had slower decompression, and didn’t have a high-compression option. LZ4 also made a lot of progress over the years; several updates to lz4 since 2012 improved search performance on decompression-heavy queries by ~50% in total.

When qgrep was made initially, all focus was on search performance, and the time it took to update the qgrep data wasn’t that important. Because of this, LZ4HC was perfect for the job - at the cost of spending more time when compressing the data, it gave better compression ratios. In later releases a few changes were made to address the slow compression performance:

- Chunk compression was moved to a separate thread so that it could run in parallel with reading files off disk and performing newline conversion and the like, and writing resulting chunk data to disk

- A lower compression level was used (which is a relatively recent addition to LZ4HC) to trade off a little bit of compression ratio for a lot of compression time.

- The default way to update qgrep data is now incremental - if no files inside a chunk changed and the chunk sizes don’t need to be rebalanced to maintain a reasonable average size, no recompression is performed

As a result, it takes 6.5 seconds with hot file cache to rebuild UE4 search data from scratch and 1.2 seconds to update a single file in it; in the latter case most of the time is spent traversing file directory structure.

Multi-threading

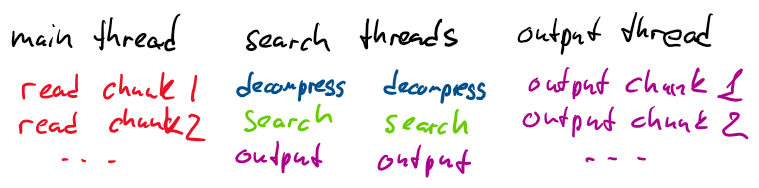

Naturally, qgrep tries to multithread the search process. There’s a single thread that reads chunks off disk, and dispatches them to a thread pool. The threads in the pool handle decompression of chunk data and the search itself.

Several important problems arise during this process.

First, the read speed and search speed can be substantially unbalanced. For example, if the data is in file cache, reading it from disk runs at memory speed, whereas decompression and search are usually slower. If the data is really large, it could be the case that the total memory impact of the chunk queue is substantial. Because of this, qgrep extensively uses a thread-safe blocking queue that has a special twist - when the queue is created, it’s being told how much total memory the queue should hold at most. Whenever an item is pushed to the queue, if the item’s memory impact exceeds the budget, the thread that pushes the item waits for “space” to become available. This makes sure that we can search arbitrarily large datasets with limited memory.

Second, search threads will generate results in an arbitrary order - each thread will generate search results in each chunk in order, but we’d like to display results from different chunks to the user in the exact same order that a single thread would. This means we need to buffer the output results - however, for some search queries the size of that buffer can be arbitrarily large. To solve this problem, qgrep uses a special purpose ordered queue - the way it works is that the producers (search threads) submit items to that queue with an index indicating the original chunk index, and the single consumer that prints the output processes items in the order indicated by this index. For example, if 3 threads finish chunks 1,2,3 quickly and the 4th thread takes a while to finish chunk 0, the output for chunks 1,2,3 will stay in memory until chunk 0 is processed and added to the queue, after which the consumer thread can process output with indices 0,1,2,3 in order.

Third, a lot of care needs to be taken to optimize memory allocations. A big source of performance issues can be allocating and deallocating large blocks of memory because on many systems doing so will repeatedly release the memory to the system, allocate it again, and trigger many page faults that can result in serializing execution, as described in my older post. This issue is solved by using a pool for large allocations (which is somewhat counter intuitive since it’s more common to pool small allocations than large ones).

Finally, for large matches, the process of highlighting the match results may take quite a bit of time - once we know there’s a match in a given line, we need to find the bounds of this match, and generate appropriate markup for the terminal output with colors. Because of this, highlighting runs in the search thread and the output chunks contain final formatted output so that the single output consumer thread only needs to print the results to the terminal.

Regular expression search

After decompressing chunk contents, we use a regular expression engine to find the match. The engine that qgrep uses is RE2; the design and performance characteristics are described here. My understanding is that the design of ripgrep is similar, but I’m not an expert on the matter - I profiled RE2 in 2012 and it was faster than other engines I tested. Since then I’ve used RE2 in some other applications and the only engine I’ve seen that could beat RE2 depending on the task was PCRE JIT, which wasn’t available in 2012 (and for qgrep specifically I’m not sure if the JIT time will pay for the increased performance since we’re interested in end-to-end time of the query and aren’t able to cache the JIT code).

The search is done on a line by line basis, however instead of feeding each line to the regular expression engine at a time, the regular expression is ran on the entire file at a time; whenever there’s a match, we output that match and jump to the beginning of the next line to continue the search. This results in optimal performance as the cost of preparing the match data is minimized, and the various scanning optimizations like memchr mentioned below can truly shine.

One notable weakness of RE2 is case-insensitive searches; it’s a general property of other regular expression engines as well - case insensitive matches generate much more complex state machines; additionally one reason why RE2 is fast is it uses memchr when trying to scan for a literal submatch of a regular expression (in the test query from this post this happens for ‘v’ and ‘K’) instead of putting one character through the automata at a time, and case insensitive searches invalidate this. Since case insensitive searches are very common, qgrep takes a shortcut and assumes that case insensitive searches only need to handle ASCII - when that assumption holds, we can transform both the regular expression and file contents to ASCII lower case. For file data, performance of this transform is critical so we use SSE2 optimized casefold function with the simple loop that processes 16 bytes at a time:

// Shift 'A'..'Z' range ([65..90]) to [102..127] to use one signed comparison insn

__m128i shiftAmount = _mm_set1_epi8(127 - 'Z');

__m128i lowerBound = _mm_set1_epi8(127 - ('Z' - 'A') - 1);

__m128i upperBit = _mm_set1_epi8(0x20);

__m128i v = _mm_loadu_si128(reinterpret_cast<const __m128i*>(i));

__m128i upperMask = _mm_cmpgt_epi8(_mm_add_epi8(v, shiftAmount), lowerBound);

__m128i cfv = _mm_or_si128(v, _mm_and_si128(upperMask, upperBit));

_mm_storeu_si128(reinterpret_cast<__m128i*>(dest), cfv);

dest += 16;

Which is a moral equivalent of computing unsigned(ch - 'A') < 26 ? (ch | 0x20) : ch, but has to work around the lack of unsigned comparisons in SSE2 by using signed comparisons instead. Note that this only works for ASCII but “proper” Unicode support was never important enough to fix; ripgrep handles this more rigorously.

Finally, regular expression search is augmented with a fast literal scanner. Very often, regular expressions start with a literal prefix (and of course sometimes the prefix is the entire expression, when you’re just searching for a specific keyword). In this case, we can use special algorithms to accelerate the search. There’s many algorithms described in the literature, and I’ve spent some time in 2012 comparing different implementations4, but outside of artificial search queries like aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaab a custom SIMD optimized search algorithm was consistently faster.

The basic idea is very simple - we can implement a very efficient SIMD scanner that scans characters 16 or 32 at a time, loads the data into SSE register, compares it to a register filled with the first character from the pattern, and does a more precise match if any match is found (the match location can be determined using __builtin_ctz intrinsic or MSVC equivalents):

while (offset + 16 <= size)

{

__m128i val = _mm_loadu_si128(reinterpret_cast<const __m128i*>(data + offset));

__m128i maskv = _mm_cmpeq_epi8(val, pattern);

int mask = _mm_movemask_epi8(maskv);

if (mask == 0)

;

else

return offset + countTrailingZeros(mask);

offset += 16;

}

This works okay in many cases, but it’s possible to improve on this. For example, if you scan for “ foo”, applying this algorithm naively will require repeatedly searching for the space (0x20) character and rejecting the match because the next character isn’t ‘f’. Instead what we can do is search for the least likely character from the pattern, and if we find it, compare characters around it for a more precise match (using SIMD), and finally confirm the match with memcmp. It’s possible to maintain the character frequency table based on the actual text we’re searching through but all source code is more or less alike, so I ended up precomputing a static frequency table and choosing the character to search for using this table. The inner loop of the matcher looks like this:

while (offset + 32 <= size)

{

__m128i value = _mm_loadu_si128(reinterpret_cast<const __m128i*>(data + offset));

unsigned int mask = _mm_movemask_epi8(_mm_cmpeq_epi8(value, firstLetter));

// advance offset regardless of match results to reduce number of live values

offset += 16;

while (mask != 0)

{

unsigned int pos = countTrailingZeros(mask);

size_t dataOffset = offset - 16 + pos - firstLetterOffset;

mask &= ~(1 << pos);

// check if we have a match

__m128i patternMatch = _mm_loadu_si128(

reinterpret_cast<const __m128i*>(data + dataOffset));

__m128i matchMask = _mm_or_si128(patternMask,

_mm_cmpeq_epi8(patternMatch, patternData));

if (_mm_movemask_epi8(matchMask) == 0xffff)

{

size_t matchOffset = dataOffset + firstLetterOffset - firstLetterPos;

// final check for full pattern

if (matchOffset + pattern.size() < size &&

memcmp(data + matchOffset, pattern.c_str(), pattern.size()) == 0)

{

return matchOffset;

}

}

}

}

If we find the least frequent character, we compare up to 16 characters around it, and finally use memcmp; this results in really good scanning performance overall. There’s a bit of overhead for short prefixes so if the prefix is a single character we use a simpler SSE matcher.

Filtering searched chunks

With all of the optimizations above, when the data set is in filesystem cache and you have a few fast CPU cores, the searches are very quick as witnessed by the performance of the “bruteforce” variant. However, when comparing to Google CodeSearch I noticed that while the worst case search performance there is really bad (substantially worse than ripgrep), the best case is really good, easily beating qgrep. This is because it uses an index based on ngrams5 - for each unique 3-gram (3 consecutive characters) of a string it keeps the list of files that have this ngram anywhere. Given a regular expression, RE2 can produce a set of substrings that need to be in the string for it to match the expression (it’s slightly more complex than that in that it can produce a literal search tree); CodeSearch uses this to find the list of files that match all required 3-grams (for example, for a file to match “vkCmdDraw”, it has to be in the lists associated with 3-grams “vkC”, “kCm”, “Cmd”, “mdD”, “dDr”, “Dra” and “raw”) and then searches in these files. Often the resulting list of files is very small, and so the matches are very quick - qgrep is fast but it’s hard to search through a gigabyte of data faster than it takes to search through a few files.

I wanted qgrep to be faster for cases where an ngram index works well, but I didn’t want to compromise the worst case performance. When profiling qgrep bruteforce on the query from this blog post, the main bottleneck is LZ4 decompression, which is ~3x slower than regular expression search (which is mostly dominated by the fast literal matcher described above). Thus if we want to save time, we need to avoid decompressing the chunk entirely - since files are compressed as a single blob, this means that we need to know ahead of time that no file in the chunk contains the given string.

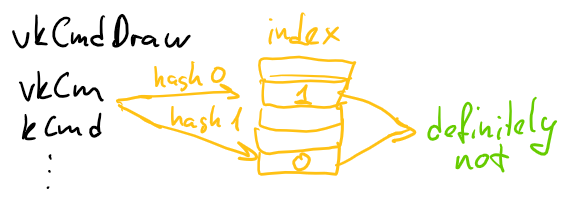

What’s more, we’d like to determine this using minimal extra time and data - while we could store some sort of ngram index, it can take quite a bit of space. Which means that this is a perfect usecase for a Bloom filter.

Bloom filters are a neat construct that allows us to spend a very small amount of memory and time to answer a question: does a given item belong to a given set? The catch is that the result can contain false positives - the answer to “is this item in the set?” is either “definitely not” or “maybe yes”.

Surprisingly, this is exactly what we need. Each chunk stores an index - a Bloom filter that contains all ngrams (after some experiments I settled on 4-grams) from all files in the chunk. When reading chunks from the file, we read the chunk index first, and check all ngrams from the regular expression - if any ngram is “definitely not” in the index, we can skip the entire chunk - we don’t even need to read it from the file, which means we save some I/O time!

The index is built when the chunk is constructed & compressed; the index is built such that the size of the index is 10% of the compressed data size to limit the worst case impact of the index; based on this size we estimate the number of Bloom filter hash iterations that is optimal for the false positives rejection rate - the Wikipedia article contains details on this. The index search itself is so fast that it’s done as we read the chunks in the main thread.

The efficiency of the index is highly dependent on the query, of course. For some queries we end up reading ~10% more data from the file and not discarding any chunks (which generally has minimal impact on the overall search performance). For many queries though it’s highly effective - for the query from the example in this post, we end up filtering on ngrams for both “vkCmdDrawInde” and “KHR = 0” strings; as a result, out of 1903 chunks in UE4 data set, we only need to decompress and process 6. Most of the resulting search time is spent reading chunk index data (all 20 MB) which can probably be optimized by packing the index data more tightly and/or using mmap, but tight packing makes incremental updates more challenging and I somehow never got around to implementing mmap support.

Note that for the 6 chunks that have a potential match (that’s ~3MB of source text), only one chunk has an actual match - because of the fact that Bloom filter isn’t precise and we compute it for all files in a chunk at once we waste a bit of time on unrelated data, but this allows us to not compromise the worst case search performance which is great.

Conclusion

Searching large volumes of source code using regular expressions is an interesting problem. There are several possible designs - ripgrep uses raw file access and tries to optimize that as much as possible; codesearch uses a trigram index in hopes that it results in minimal number of files so subsequent optimizations aren’t as interesting; qgrep tries to accelerate worst case searches by reducing the filesystem performance impact as much as possible and adding a pseudo-index on top.

Should you use qgrep? I don’t know! Compared to ripgrep, the need to maintain an up-to-date database is definitely a usability issue (although qgrep watch can make this less painful by adding modified files to the special “changed” file list and occasionally updating the database) and the commandline interface is somewhat arcane. Compared to codesearch, qgrep seems like a win but if you have 100 GB of data to search through you probably really need a “real” index. In any event, the goal of this post isn’t to advertise qgrep - it’s to talk about some interesting optimization techniques used in its implementation.

Of course, if you aren’t using qgrep, you’re missing out on this sweet sweet Vim plugin built entirely in Vimscript:

-

You would think that another option is Visual Assist or equivalent tools; however, this only works for the currently selected platform/configuration which, in a cross-platform codebase, isn’t always sufficient; it also is restricted to C++ symbols and has its own scaling challenges in a codebase with way too much source code. ↩

-

This was back when codesearch was written in C++ I think; the Go version looks impressively fast these days, but I haven’t spent a lot of time using it to know how it fares on a wide range of use cases. ↩

-

Some people who worked on EA codebase at the time used another tool called qgrep; it was closed source/proprietary and wasn’t as fast as I thought it should be - it was basically a regular expression engine that ran on the .tar.gz archive of the code. I decided to start with the same name in hopes that I can find a better name later, but never got around to it. I also inherited the command line structure from this tool because I wanted something that people on the team who wanted faster search could immediately use. ↩

-

I think I used an earlier version of SMART but I may be mistaking it for some other string search algorithm collection. ↩

-

This process is described in detail here: Regular Expression Matching with a Trigram Index. ↩

| « Small, fast, web | Robust pipeline cache serialization » |