Measuring acceleration structures

31 Mar 2025Hardware accelerated raytracing, as supported by DirectX 12 and Vulkan, relies on an abstract data structure that stores scene geometry, known as “acceleration structure” and often referred to as “BVH” or “BLAS”. Unlike geometry representation for rasterization, rendering engines can not customize the data layout; unlike texture formats, the layout is not standardized across vendors.

It may seem like a trivial matter - surely, by 2025 all implementations are close to each other in memory consumption, and the main competition is over ray traversal performance and new ray tracing features? Let’s find out.

Experimental setup

It’s going to be difficult to make any generalized claims here; and testing this requires using many different GPUs by many different vendors, which is time consuming. So for the purpose of this post, we will just look at a single scene - Amazon Lumberyard Bistro, or more specifically a somewhat customized variant by Nvidia which uses more instancing than the default FBX download.

The results are captured by running niagara renderer; if you’d like to follow along, you will need Vulkan 1.4 SDK and drivers, and something along these lines:

git clone https://github.com/zeux/niagara --recursive

cd niagara

git clone https://github.com/zeux/niagara_bistro bistro

cmake . && make

./niagara bistro/bistro.gltf

The code will parse the glTF scene, convert the meshes to use fp16 positions, build a BLAS for every mesh1, compact it using the relevant parts of VK_KHR_acceleration_structure extension, and print the resulting compacted sizes. While a number of levels of detail are built as the scene is loaded, only the original geometry makes it into acceleration structures, for a total of 1.754M triangles2.

The builds are using PREFER_FAST_TRACE build mode; on some drivers, using LOW_MEMORY flag allows to reduce the BLAS size further at some cost to traversal performance, which we will ignore for now.

Experimental results

Running this on the latest (as of end of March) drivers of all respective vendors, on a host of different GPUs, we get the following results; the total BLAS size is presented alongside approximate “bytes/triangle” number - which is not really correct to compute but we will do this anyway.

| GPU | BLAS size | Bytes/triangle |

|---|---|---|

| AMD Ryzen 7950X (RDNA2 iGPU) | 100 MB | 57.0 |

| AMD Radeon 7900 GRE (RDNA3) | 100 MB | 57.0 |

| AMD Radeon 9070 (RDNA4) | 84 MB | 47.9 |

| NVIDIA GeForce RTX 2080 | 46 MB | 26.5 |

| NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3050 | 45 MB | 25.7 |

| NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090 | 45 MB | 25.7 |

| NVIDIA GeForce RTX 5070 | 33 MB | 18.8 |

| Intel Arc B580 | 79 MB | 45.0 |

| Apple M43 | 123 MB | 70.0 |

Now, that’s quite a gap! The delta between earlier AMD GPUs and the latest NVIDIA GPUs is 3x; comparing the latest AMD and NVIDIA GPUs, we still see a 2.5x disparity in memory consumption. Intel4 is a little ahead of RDNA4, at 2.4x larger BLAS vs NVIDIA.

Now, this table presents each BLAS memory consumption as a function of the GPU - it’s clear that there’s some effect of the GPU generation on the memory consumption. However, another important contributing factor is the software, or more specifically the driver. For AMD, we can compare the results of the various driver releases during the last year, as well as an alternative driver, radv5, on the same GPU - Radeon 7900 GRE:

| Driver (RDNA3) | BLAS size | Bytes/triangle |

|---|---|---|

| AMDVLK 2024.Q3 | 155 MB | 88.4 |

| AMDVLK 2024.Q4 | 105 MB | 59.9 |

| AMDVLK 2025.Q1 | 100 MB | 57.0 |

| radv (Mesa 25.0) | 241 MB | 137.4 |

As we can see, over the last 9 months, BLAS memory consumption on the same AMD GPU and the same driver codebase has progressively improved by 1.5x6, whereas if you use radv, your BLAS consumption is now 2.4x larger than official AMD drivers, not to mention the latest NVidia GPU7.

Well… that’s certainly a lot of different numbers. Let’s try to make sense of at least some of them.

Mental model

Let’s try to build some models to help us understand what we should expect. Is 100 MB good for 1.754M triangles? Is 241 MB bad? It’s time to talk about what a BVH actually is.

First, let’s contextualize this with how much data we are feeding in. The way Vulkan / DX12 APIs work is that the application provides the driver with geometry description, which is either a flat list of triangles, or a vertex-index buffer pair. Unlike rasterization where a vertex may carry various attributes packed in the way the application wants, for raytracing you only specify a position per vertex, and the formats are more strictly specified. As mentioned above, in this case we are giving the driver fp16 data - this is important, because on fp32 data you will likely see different results and less drastic differences between vendors.8

The index buffer is your usual 32-bit or 16-bit data you would expect to see in rasterization; however, in most or maybe all cases, the index buffer is just a way to communicate your geometry to the driver - unlike rasterization, where efficiency of your index and vertex buffers is critical, here the drivers would typically build the acceleration structure without regard to explicit indexing information.

A flat triangle position list, then, would take 6 bytes per triangle corner * 3 corners per triangle * 1.754M triangles = 31.5 MB. This is not the most memory efficient storage: this scene uses 1.672M unique vertices, so using a 16-bit index buffer would require ~10 MB for vertex positions and ~10.5 MB for indices, and some meshlet compression schemes can go below that9; but regardless, our baseline for a not-very-efficient geometry storage can be in the neighborhood of 20-30 MB, or up to 18 bytes per triangle.

A flat triangle list is not useful - the driver needs to build the acceleration structure that can be used to efficiently trace rays against. These structures are usually called “BVH” - bounding volume hierarchy - and represent a tree with a low branching factor where the intermediate nodes are defined as bounding boxes, and the leaf nodes store triangles. We will go over specific examples of this in the next section.

Typically, you would want this structure to have high memory locality - when encountering a triangle in that data structure, you don’t want to have to reach for the triangle’s vertex data elsewhere in memory. In addition, Vulkan and DX12 allow to get access to the triangle id for ray hit (which must match the index of the triangle in the originally provided data); also, multiple mesh geometries can be combined in a single tree, and for ray tracing performance it’s uneconomical to separate the geometries into separate sub-trees, so the triangle information must also carry the geometry index. With all of this, we arrive at something like this:

struct BoxNode

{

float3 aabb_min[N];

float3 aabb_max[N];

uint32 children[N];

};

struct TriangleNode

{

float3 corners[3];

uint32 primid;

uint32 geomid;

};

N is the branching factor; while any number between 2 (for a binary tree) and something exorbitantly large like 32 is possible in theory, in practice we should expect a small number that allows the hardware to test a reasonably small number of AABBs against a ray quickly; we will assume N=4 for now.10

With N=4 and fp32 coordinates everywhere, BoxNode is 112 bytes and TriangleNode is 44 bytes. If both structures use fp16 instead, we’d get 64 bytes for boxes and 26 bytes for triangles instead. We know (mostly…) how many triangle nodes we should have - one per input triangle - but how many boxes are there?

Well, with a tree of branching factor 4, if we have 1.754M leaf nodes (triangles), we’d hope to get 1.754M/4 = 438K box nodes at the next level, 438K/4 = 109K at the next level, 109K/4 = 27K at the level after that, 27K/4 = 6.7K after that, and all the way until we reach the root - which gives us about 584K. If you don’t want to use boring division one step at a time, this is about a third as many box nodes as triangle nodes, which was discovered by Archimedes around 2250 years ago.

Conveniently, this means N triangles should take, approximately, N*sizeof(TriangleNode) + (N/3)*sizeof(BoxNode) memory, or sizeof(TriangleNode) + sizeof(BoxNode)/3 bytes per triangle. With fp32 coordinates this gives us ~81.3 bytes per triangle, and with fp16 it’s ~47.3.

This analysis is imprecise for a number of reasons. It ignores the potential for imbalanced trees (not all boxes may use 4 children for optimal spatial splits); it ignores various hardware factors like memory alignment and extra data; it assumes a specific set of node sizes; and it assumes the number of leaf (triangle) nodes is equal to the input triangle count. Let’s revisit these assumptions as we try to understand how BVHs actually work.

radv

Since the memory layout of a BVH is ultimately up to the specific vendor’s hardware and software and I don’t want to overly generalize this, let’s focus on AMD.

AMD has a benefit of having multiple versions of their RDNA architecture - although there were no changes between RDNA2 and RDNA3 that would affect the memory sizes - and having documentation as well as open source drivers. Now, one caveat is that AMD actually does not properly document the BVH structure (the expected node memory layout should have been part of RDNA ISA, but it’s not - AMD, please fix this), but between the two open source drivers enough details should be available. By contrast, pretty much nothing is known about NVidia, but they clearly have a significant competitive advantage here so maybe they have something to hide.11

The way AMD implements ray tracing is as follows: the hardware units (“ray accelerators”) are accessible to shader cores as instructions that are similar to texture fetching; each instruction is given the pointer to a single BVH node and ray information, and can automatically perform ray-box or ray-triangle tests against all boxes or triangles in the node and return the results. The driver, then, is responsible for:

- At build time, producing the BVH composed of nodes that match the HW format

- At render time, building shader code that iterates over the tree, using the special instructions for node tests

While the official documentation for RT formats is lacking, we do not have to reverse engineer this as we have two separate drivers with source code.

radv, the unofficial driver which is the default on Linux and SteamOS, has very clean and easy to read code base, which defines the structures as follows:

struct radv_bvh_triangle_node {

float coords[3][3];

uint32_t reserved[3];

uint32_t triangle_id;

/* flags in upper 4 bits */

uint32_t geometry_id_and_flags;

uint32_t reserved2;

uint32_t id;

};

struct radv_bvh_box16_node {

uint32_t children[4];

float16_t coords[4][2][3];

};

struct radv_bvh_box32_node {

uint32_t children[4];

vk_aabb coords[4];

uint32_t reserved[4];

};

These should be mostly self-explanatory (vk_aabb has 6 floats to represent min/max) and mostly maps to our earlier sketch. From this we can infer that RDNA GPUs support fp16/fp32 box nodes, but require full fp32 precision for triangle nodes. Additionally, triangle node here is 64 bytes, fp16 box node is 64 bytes, and fp32 box node is 128 bytes: maybe unsurprisingly, GPUs like things to be aligned and this is reflected in these structures.

Looking closer at the source code, you can spot some additional memory that is allocated to store “parent links”: for each 64 bytes of the entire BVH, the driver allocates a 4-byte value, which will store the parent index of the node associated with this 64-byte chunk (due to alignment, every 64-byte aligned chunk is part of just one node). This is important for traversal: the shader uses a small stack for traversal that keeps the indices of the nodes that are currently being traversed, but that stack may not be sufficient for the full depth of large trees. To work around that, it’s possible to fall back to using these parent links - recursive traversal could be implemented in a completely stackless form, but reading the extra parent pointer from memory for every step would presumably be prohibitively expensive.

Another, more crucial, observation, is that at the time of this writing radv does not support fp16 box nodes - all box nodes emitted are fp32. As such, we can try to redo our previous analysis using radv structures:

- 64 bytes/triangle for triangle nodes

- 128 * 1/3 ~= 43 bytes/triangle for box nodes

- (64 + 43) / 64 * 4 ~= 7 bytes/triangle for parent links

… for a grand total of ~114 bytes/triangle we would expect from radv. Now, radv’s actual data is 137 bytes/triangle - 23 more bytes unaccounted for! This would be a good time to mention that while we would hope that the tree is perfectly balanced and the branching factor is, indeed, 4, in reality we would expect some amount of imbalance - both due to the nature of the algorithms that build these trees, that are highly parallel in nature and don’t always reach the optimum, and due to some geometry configurations just requiring somewhat uneven splits in parts of the tree for optimal traversal performance12.

AMDVLK

Given that the hardware formats of the BVH nodes are fixed, it does not seem like there would be that much leeway in how much memory a BVH can take. With fp32 box nodes, we’ve estimated that BVH can take a minimum of 114 bytes/triangle on AMD hardware, and yet even the largest number we can see from the official driver was 88.4 bytes/triangle. What is going on here?

It’s time to consult the official AMD raytracing implementation. It is more or less what is running in both Windows and Linux versions of AMD’s driver; it should probably be taken as a definitive source, although unfortunately it’s quite a bit harder to follow than radv.

In particular, it does not contain C structure definitions for the BVH nodes: most of the code there is in HLSL and it uses individual field writes with macro offsets. That said, for RDNA2/3, we need to look at the triangle node more closely:

// Note: GPURT limits triangle compression to 2 triangles per node. As a result the remaining bytes in the triangle node

// are used for sideband data. The geometry index is packed in bottom 24 bits and geometry flags in bits 25-26.

#define TRIANGLE_NODE_V0_OFFSET 0

#define TRIANGLE_NODE_V1_OFFSET 12

#define TRIANGLE_NODE_V2_OFFSET 24

#define TRIANGLE_NODE_V3_OFFSET 36

#define TRIANGLE_NODE_GEOMETRY_INDEX_AND_FLAGS_OFFSET 48

#define TRIANGLE_NODE_PRIMITIVE_INDEX0_OFFSET 52

#define TRIANGLE_NODE_PRIMITIVE_INDEX1_OFFSET 56

#define TRIANGLE_NODE_ID_OFFSET 60

#define TRIANGLE_NODE_SIZE 64

So it’s still 64 bytes; but what is this “NODE_V3” field, and what’s this triangle compression? Indeed, radv_bvh_triangle_node structure had a field uint32_t reserved[3]; right after coords array; it turns out that the 64-byte triangle node in AMD HW format can store up to 2 triangles instead of just one.

AMD documentation refers to this as “triangle compression” or “pair compression”. The same concept can be seen in Intel’s hardware as “QuadLeaf”. In either case, the node can store two triangles that share an edge, which requires just 4 vertices. The triangles do not have to be coplanar; the hardware intersection engine will dutifully intersect the ray against both and return one or both intersection points as required.

Now, this type of sharing is not always possible. For example, if the input consists of a triangle soup of disjointed triangles, then we will hit the worst case of one triangle per leaf node. And in some cases even if two triangles can be merged, if one of them is much larger doing so might compromise SAH metrics. However, generally speaking, we would expect a lot of triangles to be grouped up in pairs.

This changes our analysis pretty significantly:

- Instead of 64 bytes/triangle for leaves, we only have 32 bytes/triangle

- Since we have half as many leaves, we will also have half as many box nodes, for ~21 bytes/triangle

- And the parent link cost is accordingly reduced by half as well, for ~4 bytes/triangle

Which brings up the total to 57 bytes/triangle… assuming ideal conditions: all triangles can be merged in pairs, all nodes have a branching factor of 4 (something we know is probably false based on radv results). In reality this is the configuration that AMD driver used to run in 2024.Q3 drivers, and it had 88 bytes/triangle - 31 bytes more than expected - which is probably a combination of more box nodes than we would expect, as well as less-than-perfect triangle pairing. Another quirk here is that AMDVLK driver implements what’s known as SBVH: individual triangles can be “split” across multiple BVH nodes, effectively appearing in the tree multiple times. This helps with ray tracing performance for long triangles, and may further skew our statistics as the number of triangles stored in leaf nodes may indeed be larger than the input provided!13

radv does not implement either optimization at this time; importantly, in addition to this impacting memory consumption significantly, I would expect this also has a significant impact in ray tracing cost - indeed, my measurements indicate that radv is significantly slower on this scene than the official AMD driver, but that is a story for another time.

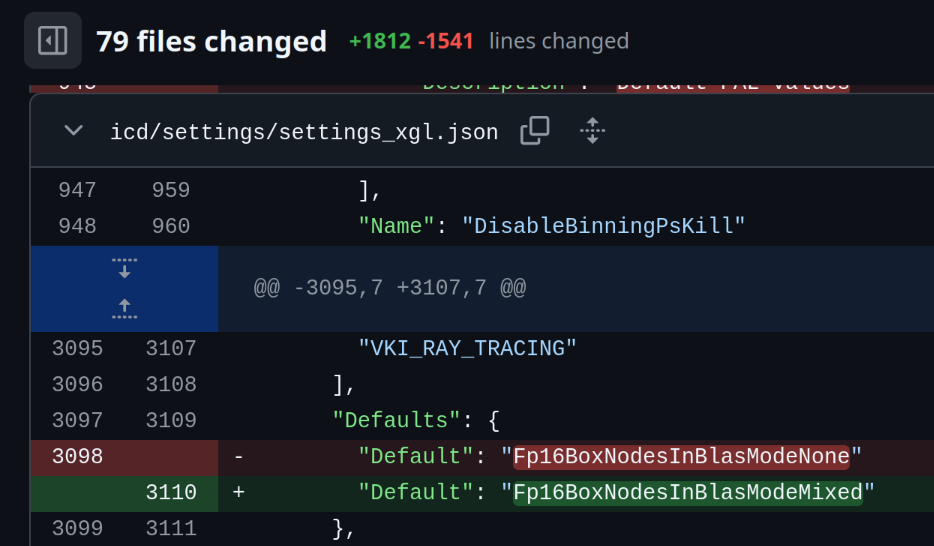

Now, what happened in AMD’s 2024.Q4 release? If we trace the source changes closely (which is non-trivial as the commit structure is erased from source code dumps, but I’m glad we at least have as much!), it becomes obvious that what has happened is that fp16 box nodes are now enabled by default. Before this, box nodes used fp32 by default, and with that change many box nodes would use fp16 instead.

There are some specific conditions when this would happen - if you noticed from the radv structs, fp32 box nodes have one more reserved field and fp16 box nodes don’t - this field is actually used to store some extra information that may be deemed important on a per-node basis in some cases14. But regardless, the perfect configuration for RDNA2/3 system seems to be:

- 2 triangles per 64-byte leaf = 32 bytes/triangle

- 64-byte fp16 box * 1/3 * 1/2 = 11 bytes/triangle

- 4 bytes of parent links per 64b = 3 bytes/triangle

… for a total of 46 bytes/triangle. This is the absolute best case and as we’ve seen before, it’s unrealistic to expect for complex geometry such as Bistro; the best results from the AMD driver use 57 bytes/triangle, 11 bytes/triangle more than the theoretical optimum.15

Worth noting that 2025.Q1 release reduced the memory consumption from ~60 bytes/triangle to ~57 bytes/triangle. Since we know some amount of memory is lost in various inefficiencies of the resulting structure compared to the optimum, it might be possible to squeeze more juice from this in the future - but given that the hardware units expect a fixed format, and some amount of efficiency loss is inevitable if you need to maintain good tracing performance, the remaining gains are going to be limited.

RDNA4

… until the next hardware revision, that is.

While RDNA3 kept the BVH format for RDNA2 for the most part (with some previously reserved bits now used for various culling flags but that’s a minor change that doesn’t affect memory consumption), RDNA4 appears to redesign the storage format completely. Presumably, all previous node types are still supported since radv works without changes, but gpurt implements two major new node types:

As is clear from the name, BVH8 node stores 8 children; instead of using fp16 for box bounds, it stores the box corners in a special format16 with 12-bit mantissa and shared 8-bit exponent between all corners, plus a full fp32 origin corner. This adds up to 128 bytes - from the memory perspective it’s just as much as two fp16 BVH4 nodes from RDNA2/3, but it should permit the full fp32 range of bounding box values - fp16 box nodes could not represent geometry with coordinates outside of +-64K! - so I would expect that RDNA4 BVH data does not need to use any BVH4 nodes, and this allows AMD to embed other sorts of data into the box node, such as the OBB index for their new rotation support, and the parent pointer (which previously, as you recall, had to be allocated separately).

struct ChildInfo

{

uint32_t minX : 12;

uint32_t minY : 12;

uint32_t cullingFlags : 4;

uint32_t unused : 4;

uint32_t minZ : 12;

uint32_t maxX : 12;

uint32_t instanceMask : 8;

uint32_t maxY : 12;

uint32_t maxZ : 12;

uint32_t nodeType : 4;

uint32_t nodeRange : 4;

};

struct QuantizedBVH8BoxNode

{

uint32_t internalNodeBaseOffset;

uint32_t leafNodeBaseOffset;

uint32_t parentPointer;

float3 origin;

uint32_t xExponent : 8;

uint32_t yExponent : 8;

uint32_t zExponent : 8;

uint32_t childIndex : 4;

uint32_t childCount : 4;

uint32_t obbMatrixIndex;

ChildInfo childInfos[8];

};

Primitive node is somewhat similar to triangle node, but it’s larger (128 bytes) and much more versatile: it can store a variable number of triangle pairs per node, and does that using what seems like a micro-meshlet format, where triangle pairs use vertex indices, with a separate section of the 128-byte packet storing the vertex positions - using a variable amount of bits per vertex for position storage.

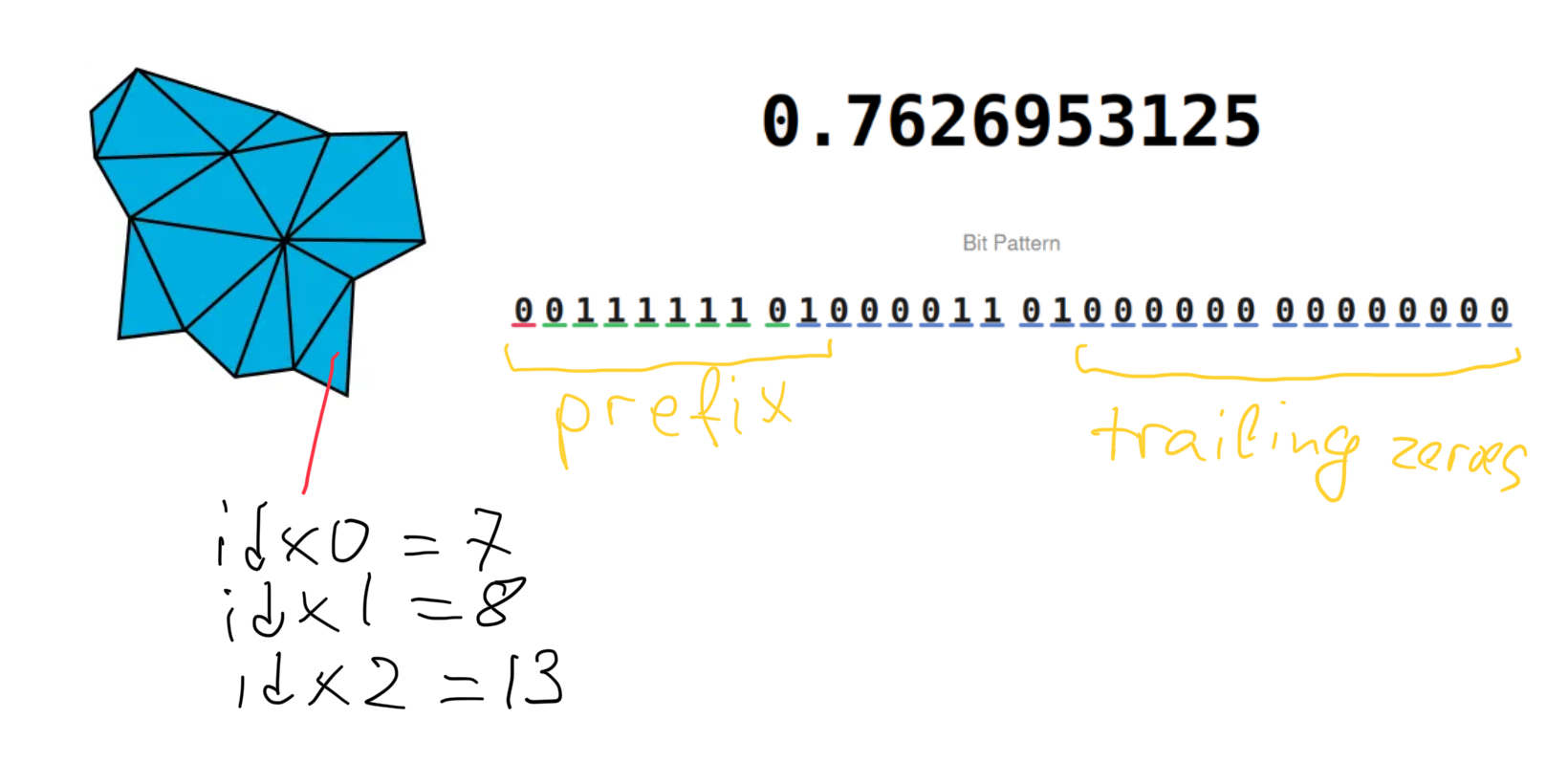

For position storage, all bits inside coordinates for a single node are split into three parts: prefix (must be the same across all floats for the same axis), value, trailing zeroes; all parts have the same bit width for the same axis across all vertices in the node. For fp16 source positions, I would expect prefix storage to remove the initial segment of bits shared between the positions which would be close together in space, and most of the trailing fp32 bits to be zero. It would probably be reasonable to expect around 30-33 bits per vertex (3 * 10-bit mantissas, with most of the exponent bits shared and the trailing zeroes removed) with that setup on average.

The triangle pair vertex indices are encoded using 4 bits per index, with a few other bits used for other fields; primitive indices are stored as a delta from a single base value inside the primitive node, similarly to positions. Notably, the triangle pair has three independent indices for three corners per triangle - so it looks like the pair does not necessarily have to share the geometric edge, which presumably improves the efficiency at which geometry can be converted to this format at a small cost of 8 extra bits for every other triangle17. The number of pairs per node is limited to 8 pairs, or 16 triangles.

It may seem that this indexed storage format is at odds with what was mentioned earlier in the post: if the driver discards initial index buffer during BLAS construction, how can it use indices here? The answer is that the BVH construction proceeds as before, and some subtrees get packed into primitive nodes. During this packing, shared vertices are identified opportunistically using bitwise equality between vertex corners - so it does not matter if the source geometry was indexed or not, as long as the triangle corner positions are exactly equal.

All of this makes it difficult to correctly estimate the optimal storage capacity of such a node. With the limit of 16 triangles, we would ideally hope to be able to pack a 3x5 vertex grid (15 vertices, 8 quads)18. If ~30 bits per vertex for position storage is accurate, then 15 vertices will take 57 bytes of storage. With each triangle pair occupying 29 bits, 8 pairs would take 29 bytes, for a total of 86 bytes. A few additional bytes are required for headers, various anchors that are used to reconstruct positions and primitive indices, and a few bits per triangle for primitive index, assuming spatially coherent input triangles - which is probably reasonable to expect to fit. Thus, a dense mesh might be able to be packed into 16 triangles per node or ~8 bytes/triangle.

Since BVH nodes are 8-wide, this also proportionally reduces the total expected number of box nodes, from 1/3 of primitive nodes to just 1/719. And given that the parent pointers are already embedded into box nodes, this gives us a best case theoretical bound of approximately:

- 128-byte primitive nodes with 16 triangles/node = 8 bytes/triangle

- 128-byte box nodes, 1/7th of 1/16th of triangles = 1.2 bytes/triangle

… for a grand total of 9.2 bytes/triangle. Now, with the actual numbers of ~48 bytes/triangle, this is clearly a wildly unrealistic goal:

- Even with BVH4, we have not seen anywhere near 4x branching factor on our test geometry in practice; achieving 8x without degrading BVH quality should be even harder

- RDNA4 acceleration units can process eight box or two triangle intersections at once; a node with 16 triangles will thus be much more expensive to process vs a node with 2. This may mean the driver decides to limit the number of triangles in each leaf node artificially to maintain trace performance.

- The description above is simplified assuming a similar high level tree structure to RDNA2/3, but in reality QBVH8 nodes can reference a subrange of a given primitive node; for example, one could imagine a single primitive node with 16 triangles, and a single QBVH8 node that, in each child, only references 2 of those triangles - which may be a different way to improve traversal performance. This means the box:triangle node ratio may be closer to 1:1 or 1:2 in practice, for 4-8 bytes/triangle instead of 1.2.

Between these factors, it’s hard to estimate the realistic expected memory consumption - but it seems plausible that we will see continued reduction of BVH sizes with future driver updates. Additionally, note that Bistro geometry has a lot of triangles with odd shapes and in general is not particularly uniform or dense. It’s possible that on denser meshes the effective bytes/triangle ratio is going to be closer to the theoretical optimum - exploring denser meshes is left as an exercise to the reader!

Conclusion

Hopefully you’ve enjoyed this whirlwind tour through the exciting world of hardware accelerated BVH storage! In summary, BVH memory consumption is highly hardware and driver specific: driver can only build a BVH out of nodes that the hardware ray accelerators natively understand, and this format varies with GPU generations; some drivers may only support a subset of hardware formats due to limited development time or tracing efficiency concerns; and specific algorithms used in the drivers for building the BVH will yield trees with different branching factors and leaf packing, which will greatly affect the results.

It will be interesting to revisit this topic in a year or so: AMD has made significant progress in both software and hardware in reducing their BVH structures, and while on RDNA2/3 it’s hard to see the BVH memory getting reduced by much, it’s not fully clear just how much headroom they have on RDNA4 depending on the scene. Similarly, it’s clear that NVidia has improved their internal hardware formats in 5xxx series, and it’s possible that there is some room left for the driver to optimize the storage further.

While standardized BVH formats would make it much easier to reason about the memory impact for raytracing renderers, it seems extremely unlikely to happen anytime soon; each vendor uses different hardware node formats with different properties and some unique features, and continues to evolve them in newer architectures. It’s unclear if these will ever converge to a common format; D3D12 experience with standard swizzle provides a cautionary tale… Something to watch here would be the future of cluster acceleration structures; while they do not solve the difference in memory consumption directly and are not supported by anyone except NVidia quite yet, they might make it easier to reason about the composition of BVH data and produce more predictable memory consumption on future GPUs - modulo trace performance concerns. Time will tell.

-

For the purpose of this analysis we will ignore TLAS; for this particular scene the memory costs of TLAS storage are very low - it only has a few hundred mesh instances; while this can be much larger in real games, I would expect BLAS storage to dominate. ↩

-

Due to instancing, the amount of geometry present in the scene is larger - around 4M; be careful with that detail if you compare other Bistro variants to the numbers presented here, as they may not match. ↩

-

The Apple number was added after the article was published originally (on April 10th); since existing translation layers like MoltenVK do not support raytracing, this is based on the separate code that shares geometry processing code and uses Metal APIs to build the acceleration structures. ↩

-

These numbers were captured using official Intel drivers on Windows, not Mesa on Linux. I don’t have Intel’s Linux numbers handy, and don’t feel like re-plugging the GPU again. ↩

-

radv is the default user-space driver for Linux systems, and the production driver for Steam Deck; all AMD measurements apart from the one explicitly listed below are taken from their official driver, AMDVLK, which is mostly the same between Windows/Linux. ↩

-

I think the gaming community affectionately refers to this phenomenon as “AMD fine wine”. ↩

-

Note that all of these numbers are not using NVidia’s latest clustered acceleration structures aka “mega geometry”; this is a subject for another post, but it doesn’t affect the analysis drastically. ↩

-

And I’m not repeating all of this again for fp32. I would argue that fp32 is quite excessive for 99% of meshes in any game, and you need to be using either fp16 or snorm16 position components if you are trying to actually optimize the memory footprint of your game. ↩

-

For example, a recently released AMD DGF SDK seems to primarily target position-only geometry, and as such might be useful for future AMD GPUs. It would just cover the geometry storage though, so we can’t use their numbers to estimate the future BVH cost; we also don’t know if this is even something that they plan to support in their RT cores. ↩

-

For Intel GPUs it looks like N=6; for AMD GPUs, N=4 for RDNA2/3 and RDNA4 has a new N=8 node. Little is known about NVidia GPUs as usual. ↩

-

I could have studied Intel GPUs more, as they do have an open source driver as part of Mesa; however, it’s unclear if their proprietary driver shares the same source, and in general I just was more interested in AMD when investigating this. ↩

-

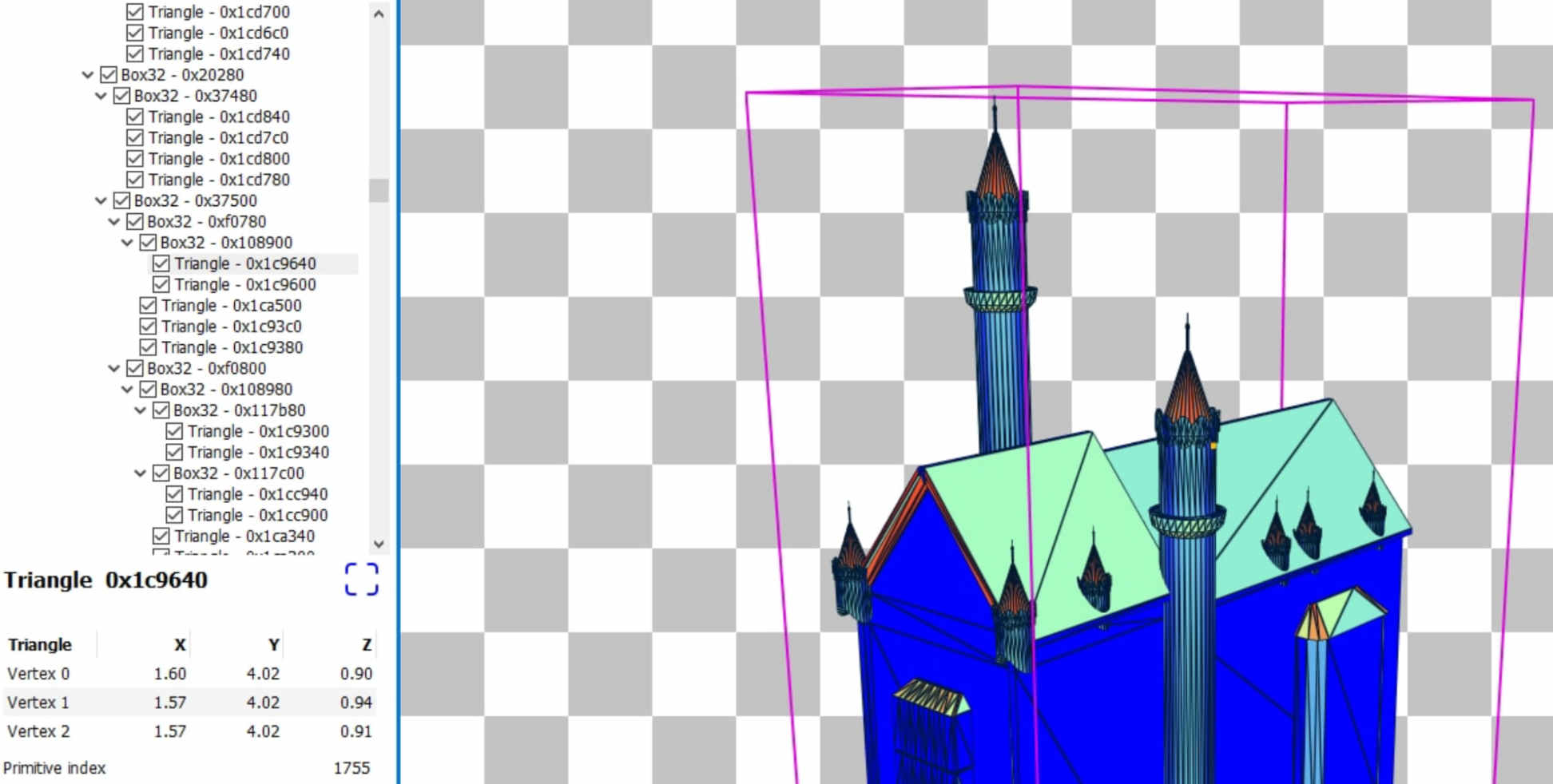

Curious readers are encouraged to explore this topic further; on AMD hardware, you can use Radeon Raytracing Analyzer to analyze the BVH as well as traversal efficiency characteristics for your workload. ↩

-

In theory it should be possible to do further tests with AMDVLK driver to disambiguate this somewhat and/or patch the code to provide more statistics, but it’s 9 PM and I’d like to finish this post today if possible. ↩

-

fp16 boxes are also naturally limited to the range of 16-bit floating point numbers; this would be a problem for some meshes with fp32 vertex coordinates, but it’s not an issue if the source vertex positions are also fp16. ↩

-

It also should be noted that gpurt sources make vague references to larger-than-64 byte triangle nodes that contain more triangles; if that can result in using more shared edges than the optimum might be lower - but this also might refer to earlier hardware revisions that never materialized. ↩

-

I have not studied this source code as extensively as the RDNA2/3 details, so all of this is an approximate description of what I can gather from skimming the code. Some details here are likely incorrect and/or missing. ↩

-

The text here is written using “triangle pair” as this is how the code references these structures, but it’s unclear if there are any restrictions on packing - it may be that AMD kept the term for convenience, or maybe earlier versions of the format used a shared edge with a smaller descriptor, and they later introduced extra bits to decouple the triangles and didn’t rename the concept. ↩

-

This math is similar to meshlet configurations described in an earlier post. ↩

-

As a generalization of Archimedes formula, sum(1/k^i) = 1/(k-1) ↩

| « Year of independence | Load-store conflicts » |